| Taking Out the Structured Investment Vehicle Garbage |

| By John Mauldin |

Published

10/21/2007

|

Currency , Futures , Options , Stocks

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

Taking Out the Structured Investment Vehicle Garbage

This week was not pretty for stocks. It all started off with the announcement of a special 80-100 billion dollar fund orchestrated by the US Treasury to bail out something called an SIV. Then Caterpillar gave negative guidance, especially on its US business, and the selling began in earnest. October 19 is still not a friendly day to the stock market. But it was a great week for bonds. One-month treasury bills dropped 60 basis points in one day in a real flight to short-term quality, and the entire yield curve moved down substantially.

But it all circles back around to the subprime mortgage mess. It is clearly having an effect on the economy (witness the Caterpillar guidance, which used the "R" word - that's recession - in association with some of its prime customers, like housing). The subprime mortgage problems, which we were assured only a few months ago would be contained, have now spread to what Paul McCulley calls the Shadow Banking System. In this week's letter, we talk about something called a Structured Investment Vehicle or SIV. There is a real crisis brewing that has serious implications for Fed policy, credit spreads, and your ability to get a loan. There is a lot of ground to cover, so let's jump right in.

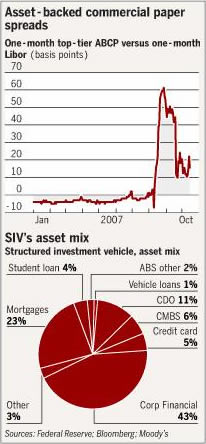

Taking Out the SIV Garbage

This week we learned that Structured Investment Vehicles or SIVs should more properly be termed SIGs or Structured Investment Garbage. Several SIVs worth over $20 billion are closing shop, and investors will lose money. More SIVs are selling assets to meet loan demands. SIVs had issued at the peak about $400 billion worth of asset-backed commercial paper. The total of asset-backed commercial paper was $1.2 trillion. Since July, that has plummeted, nose-dived, crashed to $888 billion, and is on its way to a small fraction of that. In effect, we are taking a trillion dollars of financing for a wide variety of things we need, like credit cards, autos, homes, and corporate loans out of the credit market. That is going to have an impact.

But I don't want to get ahead of myself. Let's start at the beginning. What is an SIV and where do they come from? Who owns them? Why do they exist?

We can blame the Brits. In 1988, two London bankers left Citigroup to start this industry. Today they run the largest SIV, called Gordian Knot, worth $57 billion. Essentially, an SIV allows a bank to take assets off its books and reduce the bank's capital requirement.

Why would they want to do that? Money, of course. Let's say you create $100 million in credit card or corporate debt and/or make a loan for that debt to another company. Not only do you get the interest, but you get nice juicy fees. But because of banking regulations you are only allowed to make loans as long as you have sufficient capital to protect depositors against a loss. The bank has to risk its capital, and not yours or ultimately the taxpayers'.

And those loan origination fees are quite nice. You want to make more loans. So, you move the loans off your books into the SIV. Typically, the SIV is composed of three different layers of risk. The first is the "equity" tranche, often as small as 1%. Then there is the mezzanine tranche, which can be anywhere from 4-7%. Then there are the people who lend the money to the SIVs in the form of commercial paper. Their risk is determined by the documents which formed the SIV to begin with. We will deal with that in a moment, as this is important.

Now, because you can get an AAA rating from one of your local neighborhood rating agencies, you can sell what is known as commercial paper for very little over government bonds. Commercial paper matures in 270 days or less. And you can sell a lot of it. In fact, you can easily leverage your SIV 10-15 times or more. Then you take that money and buy longer-term paper which pays higher rates, and you get to keep the difference between the cost of your money (the commercial paper) and the interest you get on your loans, which is called the spread.

If you get a spread of 4% and leverage it up 10-15 times, that is not a bad living, especially if you are investing in safe investment-grade paper. And in the beginning, the spreads were high. Life was good. So the banks decided to get in on the deal. Citibank had over $100 billion in SIVs, though that has dropped to $80 billion in the past few months. And if you run the SIV, you get to make more fees.

That is the good news. What's not to like? All perfectly legal and proper. The bad news is less clear. An SIV is a bank. Its "depositors" are the buyers of its commercial paper. Its capital is from the equity and the mezzanine tranches. If there is a run on the bank, meaning that its ability to attract commercial paper is compromised, then (depending on the legal documents which created the SIV) the originating bank might have to take that bad paper onto their books, giving them losses. Even if they are not technically required to do so, they probably will have to. If they don't, it is an invitation to lawyers to go after them.

The Financial Times had the following chart, which gives us an idea of what might be in a SIV.

All sorts of assets. Most of them quite good. In a conversation with Paul McCulley about this, he called them the "good children," and I think we will stick with that. But look at that asset mix. Notice that there are mortgages and CDOs which may contain mortgages in there. Now, most mortgage paper is quite good. But as we have learned, there are some problem kids in the mortgage world, known as the subprimes.

If you are a lender in the commercial paper market, you are getting less than 1% for your risk over risk-free assets. And if there is less than 5% equity, and if there are enough subprime loans in the mix, you might lose some of your money. Or almost as bad, the SIV may decide that they cannot pay you back on time as they sort through their assets. So you decide not to "roll over" your paper when it comes due. "Just give me my money and I will put it to work somewhere else, thank you very much."

The Rhinebridge to Nowhere

This is not just a US bank problem. "Rhinebridge Plc, a structured investment vehicle run by IKB Deutsche Industriebank AG, said it may not be able to pay back debt related to $23 billion in commercial paper programs. Rhinebridge suffered a 'mandatory acceleration event' after IKB's asset management arm determined the SIV may be unable to repay debt coming due, the Dublin-based fund said in a Regulatory News Service release. A mandatory acceleration event means all of the SIV's debt is now due, according to the company's prospectus.

"Rhinebridge, which was forced to sell assets after being shut out of the commercial paper market, said it must now appoint a trustee to ensure that the interests of all secured bondholders are protected." (Bloomberg)

This was a fund that was set up in June of this year. It is less than five months old. From the PR which accompanied the offering, apparently delivered with a straight face:

"The vehicle's unusual three-tier capital structure is designed to reduce the probability of enforcement and will allow an expected launch size of US$2.5bn. IKB has a strong co-investment commitment in the capital notes.

"Although a new SIV manager, IKB has successfully advised an ABCP conduit for five years. The team has a strong track record in managing the asset classes targeted for the portfolio, which is expected to launch with a high home equity loan exposure.

Rhinebridge's portfolio will comprise approximately 33% of seasoned triple-A, double-A and single-A bonds, as well as 67% new issue triple-A bonds."

So, this fund was leveraged about 10:1. Now, here's the kicker. Fitch Ratings gave Rhinebridge Plc's commercial paper and medium-term notes expected ratings of F1+ and triple-A respectively. The agency also assigned its senior capital notes, mezzanine capital notes, and combination notes expected ratings of triple-A, single-A and triple-B respectively.

This was last June, gentle reader. This was after the Bear Stearns problems. The problem with mortgage paper was apparent. And maybe they did indeed buy mortgage paper that will eventually turn out to be good children. But, as I said, if you are a buyer of commercial paper, and you are sitting on the desk that makes the decision which paper to buy, it is a career-ending decision to buy anything that might have subprime mortgage paper in it.

And since these SIVS are almost totally opaque, who knows what's in there? Further, for a lousy 1% spread, do you want to spend the time investigating? Do you really trust a rating agency to know what mortgage bonds are really worth? The market is voting with its feet and rushing out the door. The SIV commercial paper market is going away, at least for the immediate future.

The $100 Billion Superfund to the Rescue?

This Monday, Citibank, Bank of America, and JP Morgan Chase announced they intend to set up an $80-100 billion fund which would buy the "good children" of SIVs that are in trouble. As illustrated below (from the Wall Street Journal), they will offer to buy an asset (one of the good children) for $.94 cents plus a 4% note. There are about $400 billion in SIVs, so if they can actually raise the money, it would be a large chunk of the market. Remember, Citigroup has about $80 billion. As I will outline below, I do not think they plan to sell their own good assets into this fund.

Now, let's first assume these banks, and the others that will join them, are not doing this out of the kindness of their hearts (associating investment bankers and hearts is an oxymoron), even if the US Treasury called them together and suggested they cooperate and "play nice in the sandbox." So, what's the motive? I think there might be several.

Let me note even though the Treasury Department called the lunch meeting which started this process, this is not a government bailout. Robert Steele, the Treasury Department's undersecretary for domestic finance, made that clear when asked at the meeting whether the government would kick in some money. He said, "We bought the sandwiches, and that's it."

At the September 13 meeting, everyone agreed there was going to be a massive liquidation of assets in the coming year. What Steele wanted was for there to be an orderly liquidation. Leaving aside the odd note that it was the Treasury Department and not the Fed who called the meeting, let's get into the reasons for this fund. Let me be clear that this is speculation on my part.

I do not think it is to directly bail out Citigroup, B of A, or Morgan. They are going to take some losses to the extent that their SIVs have subprime exposure, as will every SIV and bank sponsor. If there is (speculating) 5% of subprime debt in their SIVs (and no one knows), Citi can easily absorb that. This is a bank that made almost $30 billion pre-tax last year. Annoying to shareholders, but not a capital problem.

I think the problem is elsewhere, and especially in Europe. There are a lot of Rhinebridges out there. We will see a lot more announcements of SIVs being closed in the next few months. One smaller fund in London called Cheyne has $6.6 billion in debt. Cheyne Finance's managers said its assets are worth 93% of face value, enough to pay back all of its $6.6 billion of senior debt, S&P said. CDOs of asset-backed securities make up 6 percent of Cheyne Finance's holdings. The commercial paper gets paid. The equity portion is a total loss and the mezzanine tranche gets whacked.

Don't Ask, Don't Sell

Mike Shedlock came up with the great line that the Superfund is really a fund that allows the banks to postpone marking to market. Don't ask what the paper is worth, and don't sell it so we don't have to mark down our own paper.

If all the funds which need to raise cash to pay back their commercial paper rush to the market, even the good children could get punished. My sources tell me there is plenty of appetite to buy good assets for 98 cents on the dollar at market prices, even without a Superfund.

And there probably is. So why would anyone sell their good assets to the Superfund for $.94 cents and a funny paper note if they can get 98 cents? So why go through the process of creating the Superfund?

Because of uncertainty. "Probably is" is not good enough if you are the Treasury Department or a money center bank. You do not want to see good assets selling in some kind of market panic for $.85-$.90 on the dollar. If you are a bank, that means you have to mark the assets on your books down to the market price and have to balance your capital ratios. You sell equity to raise more money or you make fewer loans. Either one is not going to make shareholders happy. And it could produce a credit crunch that would guarantee a recession.

The large majority of the assets in most SIVs are good children. The only way they sell at low prices is if there is a panic. So, the Superfund puts a bottom price to the market. Pardon me for being cynical, but I bet that $.94 plus a 4% note is a mark-down the big banks can live with. It also is an opportunity to make a nice profit on holding the good children to maturity. There are some very caustic comments from the heads of European banks about the potential profits in the Superfund.

The Superfund does not solve the problem of what to do with the subprime debt. Those losses are going to find their way onto the balance sheets of the banks eventually.

But what it does do is buy time. Instead of having to take all that debt (both good and bad) from day one, it strings things out. If you bring those loans back into your bank, it means you have less capital to lend. If you can stretch out the process, it allows you to absorb the losses more easily.

There is in fact a kind of precedent. In the '70s and very early '80s, US banks made enormous loans to South American countries formerly known as banana republics. In many cases, they had loans outstanding that were 130-150% of their total capital. The countries made it quite clear they had no intention of paying. Paul Volker winked at the problem, as marking those loans to market at that time would have meant the end of the financial world. Inflation was high, interest rates were higher, and the banks were poorly capitalized as it was, still reeling from two back-to-back recessions.

As my friend Louis Gave points out, the Fed came up with the fiction that sovereign countries could not default, so therefore the banks carried the assets at 100% of book value. It was not until 1986 that John Reed at Citibank (a little irony) broke ranks and started to sell his debt. That allowed for Brady bonds and all the rest.

But the point is that it took time for the banks to be able to handle their problems. Now, I would argue that currently banks are in the best shape ever. Citibank has $120 billion in equity. But I can imagine they would like some time to absorb the capital they will eventually have to put back on their books.

Now, other banks that have no exposure to the SIV problems might wish to get a little more market share and would wish for a faster mechanism. But that is the free market. If Citi, B of A, and Morgan (and Wachovia has said they are interested) want to come up with a plan that helps them while taking some of the risk of a panic out of the market, then fine. As long as my tax dollars get nowhere near the fund.

If their idea is not all that good, there will be no market for it. I can guarantee you that other banks are not going to help if it is not in their best interest. The market will decide how to solve the problem. If a Superfund is part of the mechanism, then so be it.

However, what I do not want to see is a delay in pricing assets. Until assets get priced correctly, the market will not function properly.

The Shadow Banking System

Paul McCulley wrote last month about the Shadow Banking System. SIVs are part of that system, buying all sorts of credit. They are part of the reason that credit spreads went as low as they did. Now we are seeing credit spreads widen as risk is being repriced, in part because of their exit from the market. That means your credit card interest rate is going up, as well as student loans, car loans, etc. It also means that credit standards are going to get tighter, as there will be less money for a period of time.

That will add additional pressure to consumer spending and be a drag on the economy. That is another reason I think the Fed will cut rates again and again. They will not stop cutting until it becomes clear we are not going into recession. We will see a "3 handle" (meaning that the Fed fund rate will start with a 3 from the current 4.75%) in four FOMC meetings or less.

Other conduits will step in eventually. There is a lot of capital in the world seeking a return. But until confidence is restored, credit, and especially consumer credit, is going to get tighter in a lot of areas. This is just one more reason to suggest we are heading for a Muddle Through Economy.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|

|