| How Do You Spell Stagflation? |

| By John Mauldin |

Published

11/17/2007

|

Stocks , Options , Futures , Currency

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

How do You Spell Stagflation?

This week we look at inflation. Is it just over 2%, giving the Fed room to cut rates, or will it be closer to 4% by the next FOMC meeting, making a rate cut problematic? How do they get those numbers? When and how can two opposite things be true at the same time? The answer depends on how many dimensions you are living in when you are asking the question. The Fed is going to be faced with a very difficult decision at its next meeting, and the results of their deliberations will be felt by you.

How do You Spell Stagflation?

I wrote this summer that it was likely that we would see inflation as reported in the Consumer Price Index rise dramatically in the fourth quarter. This is due to the very low year-over-year comparison numbers of last year's fourth quarter. We got the CPI numbers yesterday, and we did indeed see a rather uncomfortable rise in inflation, just as I predicted. "Headline" inflation is at 3.5% over the last 12 months, well above anybody's comfort level, and "core" inflation (inflation without food and energy in the numbers) is at 2.1% over the same period.

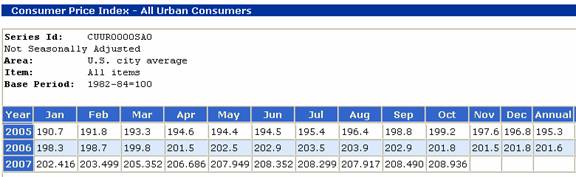

It is likely to look worse in the coming months, at least in the statistics. To see why, let's go the table below from the Bureau of Labor Statistics which creates the CPI.

The monthly numbers are the index for inflation. Since the base is from 1982-84, we can see that sometime last year prices doubled over the last 25 years. But it certainly feels like it has been more. We will look at how those numbers are created in a minute, and whether we can attach much credulity to them.

Now, here is what to notice in the table. The number for December is the same as the number for October. Since the beginning of this year we have seen a steady rise almost every month. If you assume inflation is running at 2%, this would mean that the November number would yield a 3.8% inflation rate and would be closer yet to 4% for December.

If you extrapolate the inflation of the past two months for the next two months, that would take inflation slightly over 4% as we go into the next two Fed meetings. Yes, we all know the Fed prefers to look at core inflation, but at some point you do have to pay attention to the headline number.

Today, in a speech in New York, Federal Reserve Governor Randall Kroszner said policy makers probably won't need to reduce interest rates further to help the economy weather a "rough patch" in the coming year.

"The current stance of monetary policy should help the economy get through the rough patch during the next year, with growth then likely to return to its longer-run sustainable rate," Kroszner said. Data consistent with such growth "would not, by themselves, suggest to me that the current stance of monetary policy is inappropriate."

The risks are roughly balanced between inflation and growth in his opinion. However, futures prices still suggest that the market expects an 84% chance of a rate cut at the December 11 meeting.

Cooking the Inflation Books

Just for the record, I want to state that I know, as does nearly everyone else who pays attention to the CPI statistics, that they are bogus. They do not reflect the real world that you and I, gentle reader, live in. So, while it may look like I take them at face value, I do so only because the Fed pays attention to the number, (nod, nod, wink, wink) and makes policy based upon it. So, let's look at how the calculation of the CPI has been politicized and how much of a difference it makes, and then go on to the expectation for statistical inflation in the near future.

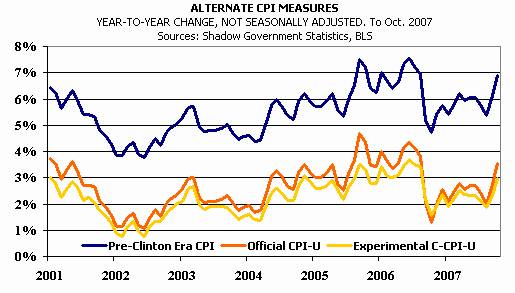

John Williams writes an excellent monthly letter on all types of government statistics called the Shadow Government Statistics at www.shadowstats.com. One of the things he points out is that during the Clinton administration, the way the BLS calculates inflation was changed. He calculates his own inflation number using the old pre-Clinton inflation model. Using that methodology suggests that inflation is at 7%. And if you use other methods, inflation might even be substantially higher. Look at the chart below.

Since the CPI is used to calculate the increase in Social Security payments and a host of other items, calculating inflation is important. In the early 1990s the argument in the press was that inflation was over-stated. Michael Boskin, chief economist in the first Bush administration, and Alan Greenspan were among the chief proponents for a new methodology of accounting for inflation.

Quoting Williams: "Up until the Boskin/Greenspan agendum surfaced, the CPI was measured using the costs of a fixed basket of goods, a fairly simple and straightforward concept. The identical basket of goods would be priced at prevailing market costs for each period, and the period-to-period change in the cost of that market basket represented the rate of inflation in terms of maintaining a constant standard of living.

"The Boskin/Greenspan argument was that when steak got too expensive, the consumer would substitute hamburger for the steak, and that the inflation measure should reflect the costs tied to buying hamburger versus steak, instead of steak versus steak. Of course, replacing hamburger for steak in the calculations would reduce the inflation rate, but it represented the rate of inflation in terms of maintaining a declining standard of living. Cost of living was being replaced by the cost of survival. The old system told you how much you had to increase your income in order to keep buying steak. The new system promised you hamburger, and then dog food, perhaps, after that.

"The Boskin/Greenspan concept violated the intent and common usage of the inflation index. The CPI was considered sacrosanct within the Department of Labor, given the number of contractual relationships that were anchored to it. The CPI was one number that never was to be revised, given its widespread usage.

"Shortly after Clinton took control of the White House, however, attitudes changed. The BLS initially did not institute a new CPI measurement using a variable-basket of goods that allowed substitution of hamburger for steak, but rather tried to approximate the effect by changing the weighting of goods in the CPI fixed basket. Over a period of several years, straight arithmetic weighting of the CPI components was shifted to a geometric weighting. The Boskin/Greenspan benefit of a geometric weighting was that it automatically gave a lower weighting to CPI components that were rising in price, and a higher weighting to those items dropping in price.

"Once the system had been shifted fully to geometric weighting, the net effect was to reduce reported CPI on an annual, or year-over-year basis, by 2.7% from what it would have been based on the traditional weighting methodology. The results have been dramatic. The compounding effect since the early-1990s has reduced annual cost of living adjustments in social security by more than a third."

Then to confuse the process even more, the BLS uses something called hedonics, from the root word hedonism. Essentially, they adjust the price of an item based on the "pleasure" or increased value you get. Thus, they don't price automobiles based on the sticker price, but on what you get for your money. If the manufacturers load in more items like new electronics or anti-locking brakes that were not standard the year before that means you are getting more value for your dollar, so therefore the price in terms of inflation goes down even though you may be paying the same or even more to get out of the car show room.

The same is true for computers. We clearly get more power every year, so for the BLS the price of computers are going down, although it seems to me that the price I pay for a top of the line computer is about the same as it was five or ten years ago.

If the government mandates an additive to gasoline that costs 10 cents more, that is not included in the inflation numbers, because we get a new, improved gasoline that pollutes less. Supposedly the pleasure of breathing cleaner air reduces the costs to our pocket book, or something like that.

My health insurance costs have tripled over the last ten years, and I know that is the experience of many of my readers. Yet, the BLS has medical costs rising by less than 50% for the last ten years. Their data suggest the cost of housing has risen by about 30% over the last ten years. Again, that is not the experience of many of my readers.

Social Security expenses are $657 billion per year. If Williams is right (and I think he is) that under the old methodology the expenses would have risen by a third, then that means we are spending $200 billion a year more. Add $200 billion to the deficit. And then watch politicians panic.

I am not one to suggest conspiracy, but if the CPI reflected the real world, the US government would be spending far more money on Social Security and a host of other pension programs. The crisis we will be experiencing in about 8 years would have already hit us. Thus, there was an incentive for leaders to find economists who could argue for new, more "progressive" methods for calculating inflation. Notice that this was done by the BLS without any protest from Congress.

None of this was done behind closed doors. The BLS, to its credit, is extremely open about how it calculates CPI, and you can get an enormous amount of detail on their web site about prices of things like tomatoes in very part of the country going back for decades.

But the way we calculate the CPI is not going to change. No administration will want to go back and add in an extra 4-5% a year to Social Security and other government pension programs. So, let's return to the prospects for a rise in the CPI in the near future, which will have policy implications for the Fed.

Gaming the Producer Price Index

On Wednesday, we got the Producer Price Index. After the above notes on the CPI, it will probably not come as a surprise that there may be some problems with the PPI. The PPI rather oddly has the price of energy going down in October. PPI is important, as it is in indication of the trend of inflation in consumer prices in the future.

As friend Bill King notes:

"Since June, BLS has energy prices declining in all three PPI stages: finished, intermediate and crude. For June finished energy goods the index is 160.9, for October 159.5; the intermediate prices are 179.9 vs. 178; for crude it's 238 vs. 232.9. BLS has energy prices DOWN 3.64% since July!!

"Oil has rallied from ~$75 to the mid-90s since July 9. Over the same period, gasoline has rallied from $1.95 to $2.35; heating oil has rallied from $2.15 to $2.55; natural gas has fallen from $8.50 to $8.25."

That means that inflation in the PPI numbers may be less than the table below, which is bad enough. Notice the increase in the change of year-over-year inflation in the index over the last 8 months.

Another table shows "core" PPI, without energy and food, and you find that core PPI is flat. Again, we are seeing almost all of the real inflation in food and energy. But with a falling dollar, do we expect food and energy prices in the US to fall as well, since much of the price of food and energy is determined on international markets?

Consumer Spending is Up, but Then Again, It May Be Down

Headline consumer spending came in up 5.2% year over year, which suggests a very respectable growing economy. But retail sales were only up 0.2% in October, which is below inflation. In other words, retail sales fell in October in real terms. But digging deeper into the numbers, we find a problem. Remember food and energy. As Greg Weldon points out, it is unlikely that US consumers bought 16% more gasoline than they did last year. The increase in spending for gasoline was all related to price. Ditto for food.

John Williams says the same analysts who want to use core inflation should also use core retail sales. And if you take out food and energy from retail sales, you find consumer spending to be flat in October. There were multiple categories like home furniture, music, electronic games, etc that were in outright declines. Most interestingly, online sales actually dropped last month. Annual sales growth dropped to its lowest number in years.

FedEx warned today that its earnings would be down due to fewer shipments and higher energy costs. The number of containers coming into the US is down. Retailers are expecting a very modest Christmas season.

So, we come to the question: Is the economy slowing and thus the Fed will cut, or is inflation rising which will force the Fed to sit tight?

A Two-Dimensional Problem

I recently spent some time with the very brilliant Columbia Professor Graciella Chichilnisky (the economist whose work created the carbon credit markets, among other things). We got to talking about the problems the Fed is facing, and she gave me a very interesting insight from a paper she had written a few years back. I am going to try and re-create it, though I am sure I will take some of the potency away in trying to put it in my simple terms.

Assume that you have an individual living in a two-dimensional world. There is only length and width, but no height. Then let's draw a line between two points exactly opposite one another above and below that two-dimensional world. At the precise point where the line meets the two-dimensional world, to the individual in that world, it appears that both points are exactly the same. Two things which would clearly be opposite to anyone living in a three-dimensional world would be equal in a two-dimensional world.

The Fed faces a problem something like that. They are living in a two-dimensional world, working with two-dimensional tools (they can cut rates or raise them) but the problems they face are multi-dimensional.

If they cut rates, the dollar will fall and import prices rise, and it will also likely have negative effects on food and energy prices. If they do not cut rates, the market will simply throw up as it will interpret that to mean the Fed is not concerned about a slowing economy.

Not cutting rates risks an economy that could easily slip into recession due to a growing risk of a credit crisis turning into a credit crunch. Usually, that means that inflation will fall. Usually, but not always.

The Fed is faced with a problem I predicted four years ago in this letter and in Bull's Eye Investing, as the Fed dramatically eased monetary conditions in an effort to fight deflation. In a word, stagflation: that terrible moment in time when an economy slows (is stagnant) yet inflation is high, limiting the monetary authority's ability to act.

With a clearly slowing economy, a credit crisis, and rising inflation, they have no good and clear choices. Whatever they do is likely to create problems in a multi-dimensional real world. I still think they cut, as core inflation is still close to their comfort zone. But if core inflation starts to rise, they will have to act. Or at least they should.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|

|