| Killing The Goose |

| By John Mauldin |

Published

10/10/2009

|

Currency , Futures , Options , Stocks

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

Killing The Goose

Peggy Noonan, maybe the most gifted essayist of our time, wrote a few weeks ago about the vague concern that many of us have that the monster looming up ahead of us has the potential (my interpretation) for not just plucking a few feathers from the goose that lays the golden egg (the US free-market economy), or stealing a few more of the valuable eggs, but of actually killing the goose. Today we look at the possibility that the fiscal path of the enormous US government deficits we are on could indeed kill the goose, or harm it so badly it will make the lost decades that Japan has suffered seem like a stroll in the park.

And while I do not think we will get to that point (though I can't deny the possibility), for reasons I will go into, there is the very real prospect that the upheavals created by not dealing proactively with the problems (or denying they exist) will be as bad as or worse than the credit crisis we have gone through. This is not going to be something that happens overnight, and the seeming return to normalcy that so many predict has the rather alarming aspect of creating a sense of complacency that will only serve to "kick the can" down the road.

This week we look at the problem, and then muse upon what the more likely scenarios are that may play out. This is a longer version of a speech I gave this morning to the New Orleans Conference, where I also offered a path out of the problems. This letter will be a little more controversial than normal, but I hope it makes us all think about the very serious plight we have put ourselves in.

Let's review a few paragraphs I wrote last month: "I have seven kids. As our family grew, we limited the choices our kids could make; but as they grew into teenagers, they were given more leeway. Not all of their choices were good. How many times did Dad say, ‘What were you thinking?' and get a mute reply or a mumbled ‘I don't know.'

"Yet how else do you teach them that bad choices have bad consequences? You can lecture, you can be a role model; but in the end you have to let them make their own choices. And a lot of them make a lot of bad choices. After having raised six, with one more teenage son at home, I have come to the conclusion that you just breathe a sigh of relief if they grow up and have avoided fatal, life-altering choices. I am lucky. So far. Knock on a lot of wood.

"I have watched good kids from good families make bad choices, and kids with no seeming chance make good choices. But one thing I have observed. Very few teenagers make the hard choice without some outside encouragement or help in understanding the known consequences, from some source. They nearly always opt for the choice that involves the most fun and/or the least immediate pain, and then learn later that they now have to make yet another choice as a consequence of the original one. And thus they grow up. So quickly."

What Were We Thinking?

As a culture, the current mix of generations, especially in the US, has made some choices. Choices which, in hindsight, leave the adult in us asking, "What were we thinking?"

We made a series of bad choices and suffered the credit crisis because of it. Now, as a nation, we are in the middle of making an even worse choice, one that will leave us with no good choices - only choices of pretty bad to awful. Let's begin with a quote from a recent client letter by my friends at Hayman Advisors (in Dallas).

"Western democracies, communistic capitalists, and Japanese deflationists are concurrently engaging in what may be the largest, global financial experiment in history. Everywhere you turn, governments are running enormous fiscal deficits financed by printing money. The greatest risk of these policies is that the quantitative easing will persist until the value of the currency equals the actual cost of printing the currency (which is just slightly above zero).

"There have been 28 episodes of hyperinflation of national economies in the 20th century, with 20 occurring after 1980. Peter Bernholz (Professor Emeritus of Economics in the Center for Economics and Business (WWZ) at the University of Basel, Switzerland) has spent his career examining the intertwined worlds of politics and economics with special attention given to money. In his most recent book, Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships, Bernholz analyzes the 12 largest episodes of hyperinflations - all of which were caused by financing huge public budget deficits through money creation. His conclusion: the tipping point for hyperinflation occurs when the government's deficit exceed 40% of its expenditures.

"According to the current Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projections, US federal expenditures are projected to be $3.653 trillion in FY 2009 and $3.766 trillion in FY 2010, with unified deficits of $1.580 trillion and $1.502 trillion, respectively. These projections imply that the US will run deficits equal to 43.3% and 39.9% of expenditures in 2009 and 2010, respectively. To put it simply, roughly 40% of what our government is spending has to be borrowed. [Emphasis mine]

"One has to ask whether the US reached the critical tipping point. Beyond the quantitative measurements associated with government deficits and money creation, there exists a qualitative aspect to such a scenario that may be far more important. The qualitative perceptions of fiscal and monetary policies are impossible to control once confidence is lost. In fact, recent price action in metals, the dollar and commodities suggests that the market is already anticipating the future."

Let me point out that the deficits for 2010 assume a rather robust recovery, and so they could turn out to be much worse, especially if unemployment continues to rise and Congress decides (rightly) to extend unemployment benefits.

The interest on the national debt in fiscal 2008 was $451 billion. Even though the debt has exploded, the interest for fiscal 2009 is down to "only" $383 billion. My back-of-the-napkin estimate says that is over 20% of total 2009 tax receipts. I guess when you take interest rates to zero and really load up on short-term debt, it helps lower interest costs. (More on that future problem later.) http://www.savingsbonds.gov/govt/reports/ir/ir_expense.htm

The fiscal deficits are projected to be about 11% of nominal GDP, which is now roughly $14.3 trillion. The Congressional Budget Office currently projects that deficits will still be $1 trillion in ten years.

Last spring I published as an Outside the Box a very important paper by Dr. Woody Brock on why you cannot grow government debt well above nominal GDP without causing severe disruptions to the overall economic system. If you have not read it, or would like to read it again, click here.

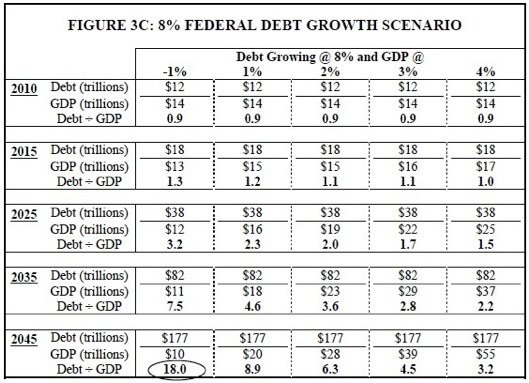

I am going to reproduce just one table from that piece. Note that this was Woody's worst-case assumption, adding 8% of GDP to the debt each year, and not the 11% we are experiencing today. The Congressional Budget Office projections are now even worse, and that assumes a very rosy 3% or more growth in the economy for the next five years. Under Woody's scenario, the national debt would rise to $18 trillion by 2015, or well over 100% of GDP, depending on your growth assumptions. Take some time to study the tables, but I am going to focus on 2015 and not the outlier years.

$1.5 trillion dollars means that someone has to invest that much in Treasury bonds. Let's look at where the $1.5 trillion might come from. Let's assume that all of our trade deficit comes back to the US and is invested in US government bonds. Today we found out that the latest monthly trade deficit was just over $30 billion, or $370 billion annualized (which is half what it was a few years ago). That still leaves $1.13 trillion that needs to be found to be invested in US government debt (forget about business and consumer loans and mortgages).

Killing the Goose

$1.13 trillion is roughly 8% of total US GDP. That is a staggering amount. And again, that assumes that foreigners continue to put 100% of their fresh reserves into dollar-denominated assets. That is not a safe assumption, given the recent news stories about how governments are thinking about whether to create an alternative to the dollar as a reserve currency. (And if I was watching the US run $1.5 trillion deficits with no realistic plans to cut back, I would be having private talks too. They would be idiots not to do so.)

There are only three sources for the needed funds: either an increase in taxes or people increasing savings and putting them into government bonds or the Fed monetizing the debt, or some combination of all three.

Now the Fed is in fact monetizing a portion of the debt as part of its quantitative easing program, and US consumers are saving more. Tax receipts are way down. I can tell you there is a great deal of angst in New Orleans tonight about the Fed monetization. This is traditionally a "gold bug" conference, and many of the participants and speakers see only inflation in our future.

Long-time readers know that I think the Fed has been able to get away with its rather large monetization program because of the massive deflationary forces let loose in the world by the credit crisis, which is forcing a monster deleveraging regime all over the world. Where has all the money gone that the Fed has printed? Right back onto the Fed's balance sheet as bank reserves. The banks are not lending, so this money does not get into the system in the usual manner associated with fractional reserve banking. Until that happens, and is accompanied by increasing wages and employment, inflation is not in our immediate future.

And this brings us to our conundrum. You cannot continue to run deficits significantly larger than nominal GDP for too long without risking the demise of the economic system. Ask Argentina or any of the other nations where hyperinflation occurred, as detailed in the study mentioned above. But we are in a deflationary environment, so the Fed can monetize the debt far more than any of us suppose without risking immediate and spiraling inflation.

But there is a limit to the Fed's ability to do so without causing real inflation. First, as long as the Fed is independent, at some point they will simply have to tell Congress we can no longer monetize the debt. While I am sure that some of you doubt they would do so, the Fed officials and economists I have been around are pretty adamant about that. There is a line they will not be pushed past. It may be further than I like, but it is there.

The Fed cannot simply buy up all the debt needed to fund the government. Again, no one on the FOMC would either advocate or allow that. That would in fact start us down a very dangerous path rather quickly. Therefore, they must have a large number of willing bond buyers outside the Fed. The good news, gentle reader, is that we will find someone to buy that debt. That is also the bad news. Let's go back 30 years.

Legend now has it that Paul Volker single-handedly took the inflation bull by the horns and ripped them off. Now, it took fortitude to do that in the face of certain recession and high unemployment. Those were not fun days. But his partner in the deed was the bond market. Bond investors simply demanded higher returns, because they were really worried about inflation.

At some point, if we do not get the government deficit under control, the bond market is once again going to react. Seemingly overnight, real (inflation-adjusted) rates are going to rise, and will do so rapidly. And I am not talking about 1 or 2%. You just cannot have 8% of a $14-trillion GDP go into US government debt every year, forever, at today's low real rates.

Let's play a thought game. If you take 8% of US consumer spending and save it, and it finds its way into government bonds, you have reduced consumer spending and therefore the actual GDP. But how about those who want to invest in stocks? Foreign bonds and currencies? New businesses? Loans of all types? How much are we going to have to save to get the necessary capital? How high will the saving rate have to be to finance all those other activities in a world where debt securitization is still anemic?

Some will point to Japan and their government debt-to-GDP ratio, which will soon be over 200%, a far cry from where we are today. Why can't we grow our debt to 200%? Because the Japanese have long had a culture of saving and investing in government bonds. It's what you do to support the country. But even they will run into a wall as their savings rate continues to drop, because so many of their citizens are retired and are now selling bonds to finance retirement. They too are running massive fiscal deficits, on the order of the size of the US deficits. And does anyone really want to have two lost decades, like Japan?

How long can we go before there is an upheaval? I don't know. The markets can remain irrational or complacent for a lot longer than most of us think. It could be years. Or not. Suddenly, it will be July 2008 and the bond vigilantes stampede.

But now, we seemingly can borrow with no consequences. The deflation that is in the air, plus the lack of bank lending holds, down the normal inflation impulses. We as a nation are leveraging ourselves up. We're partying like it's still 2005. The music is playing and we are dancing. Our Congress is trying to figure out how to run even higher deficits.

At some point, the consequences will be significant. There are two paths, and it is not clear which one we will take. First, we might see inflation kick in and actual rates rise. Since so much of our national debt is short-term debt, that means yet another rise in the deficit as rates rise. Mortgage rates rise, putting pressure on the housing market. There will be even more pressure on commercial mortgages. Consumer debt will be harder to get and cost more. It will mean funding costs for businesses will rise, and that hurts employment. It would be a return to the 1970s of high interest rates and stagnant growth in a very slow-growth environment.

Second, we could see deflation kick in and, even though rates stay more or less where they are, real (after-deflation) rates could rise as they did in the '30s and in Japan.

Some of my most knowledgeable friends argue for the inflation side, and others take the deflation side. I tend to think the Fed will fight deflation until we get inflation, but the consequences will not be pleasant. There is no benign path.

How can we avoid such an upheaval? The only way is to make some very difficult choices. There have to be some adults making the choices, as the teenagers now in control clearly cannot make them.

As I have written in the past, we can run deficits of 2% of GDP for a very long time, which in a few years would be about $300 billion. It is my belief that if the bond market and world investors saw a credible plan to put us on a path to a deficit no larger than 2% of GDP, the dire upheaval that is in our future could be avoided.

But that will mean some painful choices. It is not a matter of pain or no pain, it is just deciding when and how bad it will be. The longer we wait, the worse the consequences.

Let's Play Turn It Around

There are businessmen who are called turnaround specialists. They come into companies that are sick but have a basic competency, and that with the right management can be made into viable concerns. Generally, the choices the new management makes are painful to those involved, but they are necessary if the enterprise is to remain a going concern.

So, for the next few pages, I am going to suggest some things we can do to turn the US around. They are not easy fixes, and I know a lot of readers will not like what they read or will disagree on points. But something like this is going to have to be done, or we risk killing the goose.

First, we must acknowledge the deficit is out of control, and spending must be cut. If we raise taxes by as much as the Obama administration now wants to, we will most assuredly put the country back into a deep recession in 2011. Think what raising taxes in 1937 did to a nascent recovery. A $3-trillion-dollar budget is 20% of the US economy. That is just simply too much.

Quick fact. The most credible studies show that government expenditures exert no multiplier effect on the economy. Actually, they show them to be very slightly negative. This is not just in the US. However, the tax effect has a multiplier of 3! If we raise taxes by $300 billion in 2011, that will slam the economy in the face. Further, we will collect less taxes than projected, as economic activity will fall.

You cannot cure a too much debt problem with more debt. We cannot borrow our way into prosperity. Every crisis of the past decades has been a result of too much debt and leverage and we seem to want to repeat the past mistakes, hoping that this time it will be different. It won't.

Ok, now let's play the Turnaround Hammer Game.

+ We should start with a 5% acrossthe-board cut in spending in all programs. Federal employees, except for military personnel, should see a 5% cut in pay as part of that program. The average federal worker makes $75,419 a year, while the average in the private sector is $39,751. The rest of us are taking pay cuts in the form of higher taxes. No cost of living increases, etc. We are on an austerity program and need to do what it takes. If a program is deemed too important to be cut, then another program has to be cut more.

Then the next year another 2.5% cut across the board. And then an absolute freeze on the overall budget size until the deficit is 2% or less of GDP.

+ Social Security must be fixed now. We all know that it is going to have to be done, so why not just do it? Means testing should be a part of the mix. As an idea, for every $10,000 in income a retiree has, he gets $1,000 less in SS payments. And increase the retirement age down the road. When SS was launched, retirement age was 65. But the average life span was 65. There are other things we can do, but whatever our poison of choice is, we need to take it.

+ Medicare must be revised, with real health-care reform. The national debt is $56 trillion if we count unfunded liabilities, much of which is Medicare. It will become a nightmare around the middle of the next decade. Adding more expenses now without cutting elsewhere makes no sense. If we kill the goose, no one will get anything excect very empty promises.

Side note: there actually is a lot of waste in the system. Software should be written that analyzes every patient and procedure and produces an outcomes-based analysis of what is reasonable, rather than throwing every test at every patient. And the government should make sure, even if it has to spend the money, that the updated system is in place in every hospital and clinic in the country. And doctors should be given access to it so they can decide what type of care is appropriate to prescribe. And health-care reform means tort reform.

Today, I got a note from a friend of mine who just had yet another heart attack. It seems his stent is now blocked by 50%. He is a vet, and his primary care is the Veterans Administration. The Veterans Hospital system will not do a procedure to unblock the stent until it is 70% blocked. He does not have any money, so he is simply waiting to have another heart attack. I am really looking forward to government-run health care.

+ Each year we allow almost 1 million immigrants into the US, mostly family of people already here. I suggest that for the next two years we stop that. Instead, let anyone who can buy a home, passes basic screening, and can demonstrate the ability to pay for health insurance immigrate to the US and get a temporary green card. If they behave, then the card becomes permanent after four years.

We almost immediately put a floor on the housing market, absorb the excess homes, and within a year the housing-construction market, along with the jobs that are now gone, will be back. That is stimulus that costs the taxpayers nothing.

+ While I can't believe I am writing this, taxes are going to have to rise, if for no other reason than this Congress is hell bent on raising taxes. But rescinding the entire Bush tax cuts, plus adding a 10% surcharge as Congress wants to do in one fell swoop, is an absolute guarantee of a recession. So do it gradually over (say) 4 years, and then reinstitute the cuts when the deficit is under 2% of GDP. Remember the negative tax-multiplier effect of raising taxes. And the definitive work on that was done by Obama's chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, Christina Romer.

We should consider a VAT tax and a major cut/reorganization of the corporate tax. We need to encourage corporations to hire more, and you do that by taxing less. Let's make our corporations more competitive, not less. Our taxes are much higher than those of any of our major competitors. And please forget that insane carbon tax. If you want to cut emissions, do it straightforwardly by raising taxes significantly on gasoline. Don't back-door it on consumers. (And I am NOT advocating such a policy.)

+ An aggressive tax benefit for new venture-capital money that is invested in new technologies will result in new industries. The only way we can grow our way out of this mess is to create whole new industries, like we did in the late '70s and '80s. (Think computers and the internet and telecom.)

+ Unemployment is likely to continue to rise and last longer than ever before. We have to take care of the basic needs of those who want work but can't find it. Unemployment insurance should be extended to those who are still looking for work past the time for benefits to expire, and some program of local volunteer service should be instituted as the price for getting continued benefits after the primary benefits time period runs out. Not only will this help the community, but it will get the person out into the world where he is more likely to meet someone who can give him a job. But the costs of this program should be revenue-neutral. Something else has to be cut.

+ We have to re-hink our military costs (I can't believe I am writing this!). We now spend almost 50% of the world's total military budget. Maybe we need to understand that we can't fight two wars and support hundreds of bases around the world. If we kill the goose, our ability to fight even one medium-sized war will be diminished. The harsh reality is that everything has to be re-evaluated. As an example, do we really need to be in Korea? If so, why can't Korea pay for much of the cost? They are now a rich nation. There are budgetary fiscal limits to being the policeman for the world.

+ Glass-Steagall, or some form of it, should be brought back. Banks, which are subject to taxpayer bailouts, should not be in the investment banking and derivatives-creating business. Derivatives, especially credit default swaps, should be on an exchange, and too big to fail must go. Banks have enough risk just making loans. Leverage should be dialed down, and hedge funds selling what amounts to naked call options in any form, derivative or otherwise, should be regulated.

Let me see, is there any group I have not offended yet? But something like I am suggesting is going to have to be done at some point. There is no way we can continue forever on the current path. At some point, we will hit the wall. The fight between the bug and the windshield always ends in favor of the windshield. The bond market is going to have to see a credible effort to get back to a reasonable deficit, or we risk a very difficult economic environment. The longer we wait, the worse it will be.

It is not going to be easy to persuade a majority of Americans that we need to do something now. More realistically, we are going to probably have to begin to experience a crisis of some type to get politicians motivated to do something.

This last Tuesday, I spoke to the Financial Leadership Association at the University of Texas at Dallas. It was mostly undergraduates, and my assigned topic was how financial research impacts our investment decisions. In touched on the topic above, in less detail, but pointing out that at some point we are going to have to bring the deficit under reasonable control. I got some push-back, as some could not understand why we just couldn't keep running deficits, as we simply owe it to ourselves. I tried to explain, but for a few of them I was not getting through (though I think most got it). And these were the finance students! I shudder to think what the sociology department would be like.

We are not going back to normal, although it is likely we will see some form of Statistical Recovery. But we cannot get complacent. Somewhere out there is the real potential for another crisis, which will dwarf the last one. You will not want to be long much of anything when it happens, except hedged or liquid investments. Though admittedly, this could go on for a long time. I just don't know how long "long" is. Other than it will be too long and then not long enough.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|

|