This week, John Mauldin looks at two very different views of the euro, and then opposing thoughts on Spain.

Last week we talked about Greece. But the problems are more than just Greece. We look at two very different views of the euro, and then opposing thoughts on Spain. Is Spain a problem or not? And how can the US keep on spending? Is there a limit? There is a lot to cover in what has been an interesting, if confusing, week.

Germany, Greece, and Spain

Let's start with a little theater of the absurd. Quoting from a Reuters story (you can't make this up!):

"Greek opposition lawmakers said on Thursday that Germans should pay reparations for their World War Two occupation of Greece before criticizing the country over its yawning fiscal deficits.

"How does Germany have the cheek to denounce us over our finances when it has still not paid compensation for Greece's war victims?" Margaritis Tzimas, of the main opposition New Democracy party, told parliament."

This was during a debate in the Greek parliament on how to handle the Greek debt. And it was echoed by both the left and right political parties. Somehow they forgot about the German government paying 115 million deutschmarks in 1960, not a small sum back then. It seems that many Greek politicians are still in the denial stage of dealing with this crisis.

In Germany, it is becoming increasingly clear that there is little political will to bail out the Greeks without severe austerity measures that will further increase an already deep recession. But I wrote about that last week. Nothing has really changed, except that it has become even less clear how all this will unfold. But whatever happens, there is no positive outcome for the Greeks. Only less bad outcomes.

Well, a few things did happen. The rest of the EU took away the vote on some issues from Greece, and there are noises that if the Greeks do not take severe enough measures, they (the EU) will step in and take over. Now THAT would be an interesting spectacle. Just what the market likes: lots of confusion. Try selling a Greek bond in the midst of a modern Greek tragedy.

There are those, both in Europe and without, who think a default by Greece will mean the end of, or at least do serious damage to, the euro. Count me among the skeptics on that, as a default by California would not do much damage to the dollar. Greece is only about 2.5% of the Eurozone GDP. It would be a problem, and maybe even a crisis, as European banks have large Greek debt exposure; but Germany in fact could bail out its banks a lot more cheaply than bailing out Greece. And Portugal is even smaller.

I wrote in 2003 that I thought the euro (then at $.88) would go to $1.50 (it got to $1.60) and all the way back to parity ($1) over the course of many years. I still think so. It has and will be a long and rocky road. It is still not clear how all of the problems in the eurozone countries will be resolved, and by that I mean the serious entitlement liabilities they will face in the middle of the decade.

Oh, and as a reminder, I wrote last year and at the beginning of this year that the dollar was going to get stronger. I got more than a few people telling me I was, well, wrong, with varying degrees of politeness. (You need a thick skin to write this letter!)

Two Views on the Euro

My good friends David Kotok and Dennis Gartman illustrate the two sides of the euro debate. Dennis has long been a euro skeptic, and of late has been especially forceful as he writes about the problems of the euro. David runs around with serious international thought shapers in Europe. David wrote a letter to Dennis this week, and Dennis responded. I am taking the liberty of reprinting part of that conversation, as it sets up the discussion we will have nicely.

Dennis,

Most of the time you and I are simpatico in view. But this time we are on totally opposite sides. You predict the EUR is toast. I think it emerges from this stronger than ever and that the weaker system is now the deficit-ridden US. I have organized and chaired conferences and seminars in Europe for the last decade as program chair of the GIC, www.interdependence.org. The next one is in June in Paris and Prague, to which I am inviting you with this email.

In the course of this decade those meetings have ranged in location from south (Italy) to Baltic (Estonia) to west (Ireland). All of these meetings were multinational. None of them had language or cultural barriers. All of these various hosts were gracious and hospitable and welcoming. All of them had goodwill among nationals of the various European countries. None of them had internal antagonism.

Come with me in June and see this with your own eyes. Europe wants a hard currency and better economics and knows how to get it. The Greeks will end up better off and the politics will force it.

I am a euro bull. All the best. By the way, I still want you to come fishing with me.

David [Kotok]

Dennis answered.

David,

I'm writing from Calgary this morning. Nice town, and not all that cold. Nice people out here in Canada's west. I always feel better about the world when I get to the Canadian west.

We do indeed disagree on the EUR, David, and I hope you are right, but I fear you are wrong. These cultural differences are simply too great to be overcome. I have always been a EUR skeptic, and have been surprised that the whole experiment has lasted this long, but the Germans are not going to allow any of their money to be shipped to Athens to defend Greeks who have no pride in their own country [and are] tax-paying scofflaws. The German's felt put-upon by the rest of Europe when they paid for the cost of reunification entirely, and they have no intention of now paying for Greeks who thumb their noses at law and fiscal responsibility.

Right now, the market's sayin' I'm right, and for now I'm going to press the issue until the market tells me I'm wrong, David. It's all I know to do. Expecting Papandreaou to change his fiscal spots is simply not wise. He has been a profligate all his life; so too his father. It is genetic and it aint' gona' change.

Be well, my friend. We can disagree and still be impressed by one another's work. I know I am.

Dennis Gartman

Who's right? In an odd way, both of them.

Let's look at what I think is the difference between my two friends. If you read European papers and briefings by serious economists and euro politicians, the idea of the eurozone breaking up is simply unthinkable to them. So much time and effort was put into creating the euro to begin with that there is a lot of vested interest in keeping it. (And by the way, let me be clear that the world is better off with a viable euro.) When David goes to Europe, as he often does, he meets with the top tier of business, investment banking, and central banking circles. And they assure him they will figure this out. These are the thought leaders who brought the euro together in the first place.

Dennis listens to the trading floors and people in the streets. He was a man born in the trading pits. He rightly looks at the politics of Greece and Germany and says that is a "dog that won't hunt."

In the short term, a Greek default will put significant pressure on the European banking system and through that the euro. But it is not the end of the world for the euro. Ultimately, in the grand scheme of things, the value of the euro, within limits, is not significant. If it falls to dollar parity there are winners and losers, of course. European exporters will be delighted. So will be their farmers. If you are a consumer buying goods outside the eurozone, you will not be as happy.

But the valuation of the euro is not in and of itself a reason for the euro to disappear. At one time it was $.82. Then over $1.60. All currencies fluctuate, some more than others. What destroys them is political malfeasance.

What would put the euro at risk of a bad political decision? A Greek bailout without serious conditions would be the one thing that could be a very bad start to a downward spiral. If Greece is bailed out, then why not Portugal or Spain or Ireland? What about the emergency room crisis that is Austrian banks?

The line has to be drawn, and it has to be a hard line. And basically, what David is saying is that the serious leaders with whom he is in contact get it. But it is not certain how things will play out. Will Greek politicians and unions blink when faced with reality? Polls show that a majority of Greeks now favor making serious budget cuts. And the reality is that they will lose access to the credit markets if they do not make major spending cuts and get some kind of pan-European guarantee for their new debt. Losing access to the credit markets will mean even more (and immediate!) drastic cuts.

The real choice for the Greeks is whether to stay in the monetary union. Of course, leaving and defaulting on their debt also cuts them off from the credit markets. It is a sad reality they face.

The Pain in Spain

That of course brings us to the elephant in the room – Spain. While the eurozone can survive a Greek default or a serious Greek depression, Spain is another story. Spain is a very large country whose deficits, if not brought under control, could in fact tank the euro.

Spanish leaders have been all over Europe, loudly proclaiming that they are not Greece. However, their current fiscal deficit is in the same league (9%), and they have other problems. And just as Dennis and David disagree, this week I had two reports on Spain hit my inbox the same day, from two of the groups I respect the most. And they do not agree abut the future of Spanish debt.

The first was from the European team of the Bank Credit Analyst. I have been reading BCA for decades, and they have a real knack for being right. I pay attention when they write something. They are a serious research firm, and consult with the biggest firms in the world. It is not an exaggeration to say the central bankers pay attention to them.

And they think Spain is going to work out. Let's look at a few paragraphs from their latest report:

"Listen to the current market commentary and you might be forgiven for thinking that history is repeating itself. We don't want to minimize the country's woes. Unemployment has after all just breached the psychologically brutal level of 4 million.

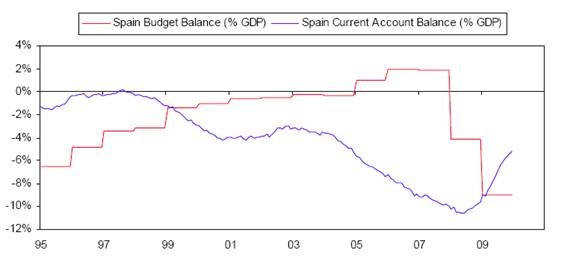

"But much of the analysis is backward looking. What the markets fear has already happened. A rerun of the Greek debt crisis is not inevitable, Spanish bonds are cheap relative to Bunds and many of the cyclical imbalances are on the mend. Spain has already undergone 18 months of painful economic adjustment. The current account deficit in relation to GDP has more than halved to 4.6% from its peak in 2008, when in absolute terms it was the second highest in the world after the US.

"The budget shortfall is beginning to roll over, a reduction plan is in place and the public debt-to-GDP ratio is 60%, barely more than half the Greek ratio. Most importantly, the inflation rate has converged with the euro zone average, one of many indicators confirming the decade-long adjustment to membership of the currency club is complete.

"Spain does not fit well into the caricature of a two speed Europe, with the south on a slow, unsustainable growth path. Its demographic profile is far more propitious to economic growth than Germany or France, never mind Greece and Portugal, and its policy makers are in many instances more vehement about the need for financial discipline. After all, it was Spain which recently attempted to get the EC to agree to penalties for countries that did not hit their economic targets, only to be blocked by Germany. If there is to be a euro crisis, it is not going to be Spain that causes it.

"... The shakeout in the labor market will bring a sharp short term jump in productivity, with policy changes providing additional help thereafter. Immigration creates the potential for Spain to grow its way back."

It was just a few months ago that I published a report from Variant Perception on the serious problems of Spanish banks. Spain has almost 20% unemployment and the government deficit is almost 9%. They have a trade deficit of 4%. Real GDP is down by 5%. Getting back to growth and a less severe government deficit is going to take some serious willpower from a socialist government. So I was glad to read that someone I respect as much as BCA thinks things will work out.

Then I read a short report by Ray Dalio and the team at Bridgewater. It is hard to get their work, but every now and then someone gets me a copy. I don't know Ray, but I have serious respect for his work. I am a huge fan. He is one of those men about whom the word brilliant can be used without risk of exaggeration. Bridgewater manages $80 billion or so for some of the largest institutions in the world. ( www.bwater.com)

So what do they write about Spain? They are not as optimistic.

"[because of the recession] ... the Spanish government decided to run big budget deficits that have been funded with big borrowings, but the more the debt increases, the closer this approach is to coming to an end. As of now, conditions are tenuous but acceptable because most investors a) are used to thinking of Spain as being safe and not having wide credit spreads and b) have been inclined to pick up yield by holding debt that was generally considered safe, so they funded these deficits with narrow credit spreads.

"We do a lot of work estimating what a country's credit spreads should be in light of its cash flows and asset values and have made more than a few bucks doing this. Based on these criteria, we judge Spain's actual credit spread to be just about the narrowest relative to what it should be on the basis of its fundamentals -- i.e., the spread is 1.4%, and we would assess the fundamentals to warrant it to be 6.5%, on the basis of fundamentals alone.

"We judge Spanish sovereign credit to be much riskier than is discounted because it seems to us that there is a high risk that Spain won't be able to sell the debt that it needs to fund its deficits, and there is virtually no chance that the government can cut spending (nor does it want to). That is because a lot of debt is coming due; the Zapatero government is weak, very socialist and supported by a collection of factions (e.g., those in states seeking independence); and the Spanish people are now politically fragmented and only care about what money the government is going to give them. Also, the private sector debt problems have largely been kept under the rug rather than dealt with via restructurings.

"In other words, 1) Spain has big debt/deficit problems; 2) it is not dealing with these problems by doing the tough, forthright things to alleviate them; 3) it doesn't have the printing press to avoid the risk of default (unless the ECB helps them); and 4) it has a narrow credit spread. Situations like this, in the past, have been associated with both debt rollover and capital flight problems.

"... Spain's external debts, have exploded without a significant offset of external assets. On net, Spain owes the world about 80% of GDP more than it has external assets. As a frame of reference, the degree of net external debt Spain has piled up in a currency it cannot print has few historical precedents among significant countries and is akin to the level of reparations imposed on Germany after World War I. We don't know of precedents for these types of external imbalances being paid back in real terms.

"On top of the debt that needs to be rolled, Spain's cash flows (current account and budget deficit) are extremely bad. Spain's current living standards are reliant not just on the roll of old debt, but also on significant further external lending.

"For these reasons, we don't want to hold Spanish debt at these spreads."

And this, gentle reader, brings us to the heart of the problem. These are two very smart research houses with opposite conclusions. Having disagreements is not all that unusual. Disagreements are what makes for horse races and markets.

But the difference is in essence the same disagreement that David and Dennis have. It is one of political nuance. BCA thinks Spain will get its act together, and Bridgewater does not, or at least not until its hand is forced by the markets (my assumption, not theirs).

The amount of pain that Spain must endure to get it fiscal house in order should not be underestimated. Wages are going to have to fall relative to northern Europe for them to be competitive. The dependence on government is going to have to be reduced. This is not going to be easy for a socialist government with a very thin coalition.

And that brings us back to Greece. While Greece can be readily bailed out (assuming they accept large budget cuts) because it is small, Spain is too big to save. The European Union cannot set the precedent that countries that do not set their fiscal houses in order will be bailed out by countries that do.

This is the nature of the End Game I have been writing about. The decisions are now political. How do we unwind the debts and the leverage? How much pain do we postpone and how much do we take on today? It is the same question for much of Europe, Great Britain (serious problems there), Japan (which is a bug in search of a windshield), and the US. We now have a limited number of path-dependent options. By that I mean the political paths chosen by the various governments will dictate the economic path we go down.

How Much Is Too Much?

And to close, I want to show a chart from today's Wall Street Journal, from a column by Daniel Henninger.

This is the definition of an unsustainable path. Spending has grown 7 times as much in real (inflation-adjusted) terms as median household income over the last 40 years. Like Greece and Spain and much of the rest of the developed world, we will be forced to make hard choices. We cannot afford to do everything that even conservatives would like, let alone liberals. We cannot fight two wars, increase spending on health care, stimulate a faltering economy, and fun a 20% explosion in federal employees in just one year, etc., etc.

Pay attention to Greece and Spain and especially Japan over the next few years. Unless the US gets its fiscal house in order, we will be next. It will not be any easier for us in five years than it is for Greece today.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.