The Housing boom and bust have been page-one news for what seems like years now. Is there anyone left in the country who doesn't know about the huge run up in home prices during 2002-06, and the subsequent "correction?"

My guess is no one. What most people may not be aware of, however, is just how unusual residential real estate has been in the current cycle. The housing boom has played an enormous role, with few truly appreciating the outsized contributions the "Real Estate industrial complex" has played in the recovery and expansion. It can politely be described as "atypical."

Since the recession ended in 2001, Real Estate has been crucial in enabling enormous consumer spending, and helping to create many new jobs. These two factors have been the primary drivers of the post-crash economy. With this economic expansion now entering its fourth year, the cooling real estate market is increasingly presenting new risks. With the peak of the boom long since past, the current inventory build up, sales slow down, and price decreases are starting to take their toll on economic activity. Given how extraordinary the boom was, we may not be in for a run-of-the-mill downturn.

Few investors seem to have fully considered the impact the boom and subsequent bust will have - for the real estate market, to equities, and to the overall economy. Today's commentary aims to correct that. We want to put Housing's surge into the broader context of this business cycle, and examine what the slowdown will mean to various economically sensitive sectors. To do that, we will look at:

- How this expansionary cycle got started;

- Why this post-recession cycle has been so unusual;

- How this housing market has been "backwards"

- Where these factors are impacting consumption, the economy, and equities.

The Background

Let's go back to the end of the last recession: The nation had suffered through a wrenching stock market crash from 2000 to '02. NASDAQ, where the hottest stocks had been, plummeted 78% peak-to-trough - on par with the 1929 crash. A mostly corporate recession followed in 2001. Companies cut back their hiring and spending. At the same time, the consumer barely paused (they account for ~70% of the US economy). The third strike was 9/11 and it's economic after-effects. All three of these events managed to drag economic activity down to anemic levels. By 2002, the US economy was looking downright sickly.

Once the US Economy was under the weather, the government prescribed the usual medicine: big tax cuts in 2001, lots of deficit spending, increased money supply, military spending for two wars, and significant interest rate cuts. This treatment is tried and true, usually effective in jumpstarting growth. Many economists would argue that left alone, the economy would eventually self-correct anyway, but let's save that discussion for another day.

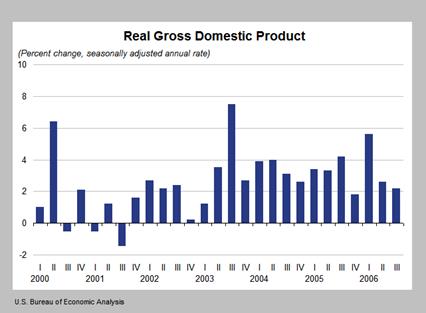

A funny thing happened on the way to the recovery: Despite the massive stimulus, nothing much happened at all. Following the Tax Relief Act of 2001, plenty of deficit spending in 2002, lower rates, and even more tax cuts in 2003, the economy was still barely limping along. Real GDP was barely positive in Q4 of 2002 (chart below). The possibility of a "double dip recession" was very real, and that was making the members of the Federal Reserve very nervous.

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) had watched Japan get caught in a decade-long recession, compounded by a nasty case of deflation. Consumers there - even more gadget loving than Americans, if that's possible - had become increasingly cautious. While the Japanese are culturally more likely to save than we Americans are, they had taken frugality to new extremes. And the less the Japanese spent, the more manufacturers and retailers slashed prices, hoping to draw them back to a consumptive mode. The longer consumers waited, the cheaper goods got. It was a vicious deflationary cycle, and once started, difficult to break.

On November 21, 2002, then Fed Governor Ben Bernanke gave a speech on the subject. It was titled "Deflation: Making Sure "It" Doesn't Happen Here." Bernanke made reference to the government's not-so-secret anti-deflation weapon:

"The U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so, the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to raising the prices in dollars of those goods and services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation." (emphasis added)

That anti-deflation speech turned out to be quite prophetic: Bernanke eventually became Fed Chair, and he put those printing presses to good use. Bond desks would nickname him "Helicopter Ben," thanks to his speech that threatened a metaphorical money drop as a way to stave off deflation.

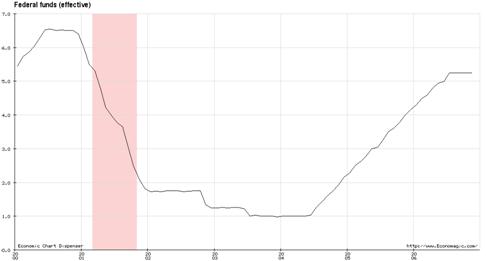

But that was still in the future. Circa 2002, the Fed was getting increasingly nervous. Under the leadership of then-Chair Alan Greenspan, rates had already been slashed from pre-crash highs of 6.5% all the way down to 1.75% - levels not seen since John F. Kennedy was President in 1962. For nearly a year, the central bank kept rates at that low level. Despite this, there was not much economic reaction.

Unwilling to take the chance of a Japanese-like deflationary spiral happening here, the Fed got panicky. Their response was that of a doctor whose patient was not getting better despite taking his meds: They upped the dosage:

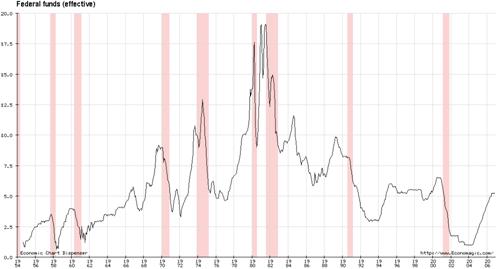

In Fed speak, that meant more rate cuts. The FOMC took rates down to 1% - a 46 year low. Then, just to make sure the patient did not going to slip back into a coma, they left rates at 1% for a full year. As the 1954-2006 chart of Fed Fund Rates (below) shows, this degree of stimulus - and for such an extended period - had never occurred before.

This unprecedented monetary stimulus had five primary impacts:

1) The initial stimulus "reflated" the economy: The ultra-low cost of capital encouraged economic activity, and GDP surged.

2) Dollar denominated asset classes were "re-priced:" Money was so cheap and plentiful, anything priced in dollars - oil, gold, industrial commodities, etc. - rallied dramatically in nominal prices.

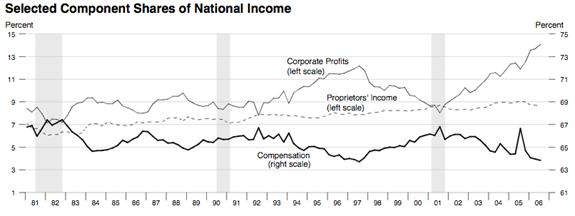

3) A new round of Inflation was ignited in just about every item in the production pipeline - with the exception of labor (this becomes important later on).

4) The Consumer aggressively used cheap debt, financing whatever they possibly could. This led to their savings rate promptly dropping below zero - levels last seen in the post-crash 1930s.

5) Major debt-financed consumer purchases - primarily homes and automobiles - saw a huge spike in sales.

More so than any other factor - tax cuts, deficit spending, increased money supply, etc. - it was the generational-low interest rates that resuscitated the economy. These other stimuli all played a role, but ultra-low rates are what dominated economic activity.

But the first rule of economics is that there is no free lunch, and the stimulus came at a price: Inflation.

Even China's explosive growth was indirectly related to FOMC actions. Chinese apparel, electronics, manufactured and durable goods makers were the prime beneficiaries of the debt fueled spending binge here. So Beijing returned the favor, buying a trillion dollars worth of US Treasuries. This helped to keep rates relatively low, even when the Fed shifted into tightening mode. Thus, a virtuous Real Estate cycle was reinforced and extended even further.

An Unusual Post-Crash Recovery: The Backwards Cycle

What is the net result of this unprecedented monetary stimulus? When viewed from a historical perspective, the expansion it created was:

--light on new job creation,

--heavy on inflationary pressures, and

--overly dependent on real estate.

Especially unusual this cycle was the "backwards" nature of the Housing Boom: In most recoveries, it's the economy that drives Real Estate. While interest rates are always significant to housing, in the typical cycle, it is job creation and wage growth that are the key metrics for residential sales. That's not how it happened this time.

In the aftermath of the 2000-01 recession, Non Farm Payroll growth was anemic. With the exception of this past quarter, Real (after-inflation) wage growth has been flat or negative. As of Q3 2006, there were only 3.5% more jobs than there was at the end of the recession. This compares very unfavorably with prior recoveries.

Consider the previous poorest showing, the 1953-54 period, which was the worst of the nine recession recoveries since WWII. Yet, even that period had Job gains more than double the current cycle: Following the 1953-54 recession, total employment gained 7.6%. Even more astounding, that relatively poor showing was actually held down by the recession of 1957-58.

To put this into context, "at this point after the previous nine recessions, there were an average of 11.9 percent more jobs in the economy than there had been at the end of the recession." (Norris) The reality is that new job creation during this present cycle has been the worst on record since WWII. And, the wage situation has fared no better: Wage gains have not kept up with inflation for most of this cycle, and have only recently edged above it.

Even with recent upward revisions to Non-Farm Payroll data, job creation and wage gains remain much worse than in prior cycles.

Then there is the issue of exotic mortgages. Enough ink has been spilled on this subject that it is unnecessary for us to go into painful detail on the subject. While the traditional 30-year fixed mortgage is still the most popular form of financing, it has lots of competition now. There has been an explosion of risky forms of finance: adjustable rate mortgages (despite rates at generational lows!), no credit-check loans, interest-only mortgages, 120% financing, piggy-bank mortgages, and all other manners of "creative" financing for sub-prime borrowers. These mortgages tend to be the first that will default.

Suffice it to say that if job creation or wage gains were actually driving Real Estate, the dependency on high-risk, exotic loans would have been totally unnecessary. Very low rates, along with a very unhealthy dollop of exotic debt, are what have been behind the biggest Housing boom since WWII - not the typical job or income gains.

The Economy Drives Real Estate, or Vice Versa?

So this cycle has seen the usual course of affairs inverted. Instead of a robust economy driving home sales and prices, it has been the exact opposite: Robust residential real estate has been what is driving an otherwise bland Economy.

With private sector job creation modest, and Real (inflation-adjusted) Wage gains flat to negative, it's obvious to us why Real Estate has run so far: The ultra-low interest rates. By taking the cost of money down to generational lows, and then leaving it there for quite some time, the Fed initiated the biggest Real Estate boom since 11 million GIs returned home from War World II, and created in the process "suburbia."

The primary gains from Real Estate were threefold: 1) Job Creation; 2) the Wealth Effect 3) Consumer Spending. Let's take a look at each.

Job creation has taken place across a wide swath of industries - much more than just residential construction. Sure, developers, builders, and subcontractors saw job growth explode. But it was far more than that. From real estate agents to mortgage brokers, from designers to contractors, plus the many employees of stores like Home Depot (HD) and Lowes (LOW), the Real Estate industrial complex was responsible for a disproportionate percentage of new job creation.

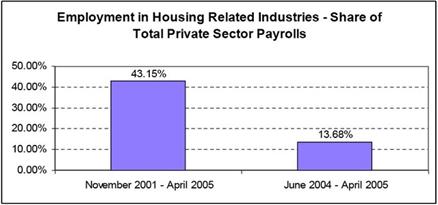

How disproportionate? According to a study by Northern Trust, from 2001 to April 2005, 43.0% of private-sector jobs creation was housing related. That's an astonishing number. But if you are still uncertain as to the impact of low rates, consider what occurred once the Fed began reversing those ultra low rates (June 2004 to present). Real Estate related job creation plummeted 68.2%.

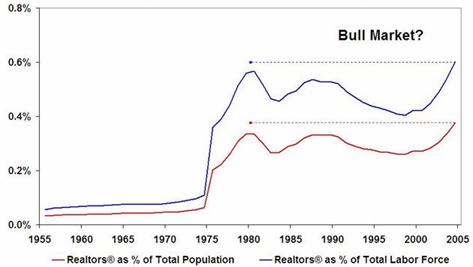

As an example of the impact that the interest rate environment had, consider those who are on the front lines of residential home sales - real estate agents. The housing market created an exploding bull market in the sheer numbers of real estate agents.

From 2001, to the housing peak in 2005, the total number of Realtors, as a percentage of the Total Labor Force, gained nearly 50%. This surpassed the peaks of the prior two booms of the '70s and '80s:

Housing's Wealth Effect

In addition to the actual dollars extracted from housing, don't underestimate the psychological impact feeling flush has on spending.

Some studies have shown how the rise in home prices has provided for 70% of the increase in household net worth since 2001. But consider how significant the psychology is: A recent study quantifies the outsized impact and multiplier effect on wealth that housing has. According to the study authors (Christopher Carroll, Misuzu Otsuka and Jirka Slacalek), an increase in housing wealth of $100 will boost spending by $9. A similar increase in stock market wealth "only" creates $4 more spending.

Considering how widespread home ownership is in the United States, this is quite significant: About 68.5% of American families live in their own homes (and some recent data puts this as high as 70%). While ownership of stocks is widespread - studies put market participation at near 50% of all Americans - for the typical family, they have a rather small percentage of their net worth in equities. Indeed, in most cases, stocks are their second or third largest asset.

So the wealth effect of home price appreciation is not only greater, it is much more widely distributed.

Where the Real Money is: Consumer Spending

The boom had a positive impact on jobs, and the income and spending that goes along with it. And the wealth effect it created was very real. But the most significant impact to the economy was Mortgage Equity Withdrawal (MEW) and the Consumer spending it enabled. This has been the single biggest element of the economic expansion. Without it, the nation would have had a flat to 1% GDP, and be on the verge of a recession.

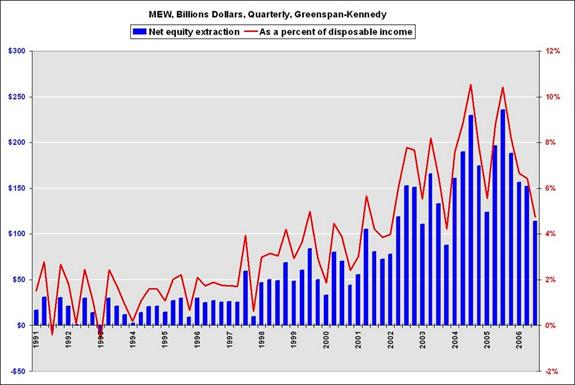

Consider what MEW had been like in the past: For most of the 1990s, the Net Equity pulled out by homeowners - either through sales, or through home equity refinancing - were fairly modest. It accounted for ~$25 billion dollars per quarter, and was about ~1% of disposable personal income.

After slumping in the late '80s and early '90s, home prices began to rise modestly. By the late 1990s, gains had returned to the historical mean. That allowed some withdrawal of equity. But even then, it remained a relatively modest amount, at $25-50B per quarter - about 2% of disposable income. Given the total GDP of the US is $12.3 trillion (2005), this amounted to only a small blip on the economic radar screen.

The impact of MEW began to accelerate once the Fed cut rates so spectacularly. By mid-2002, the quarterly average MEW was north of $100 billion - that's greater than 4% of disposable income, up nearly 400% since 1997. By 2003, those quarterly numbers were $150 billion and 6%.

Then, things exploded in 2004, as quarterly withdrawals were almost 1/4 trillion dollars, and MEW hit a peak - it was over 10% of disposable personal income. To put that into context, that's a 1000% gain since 10 years before in 1995. (see chart below)

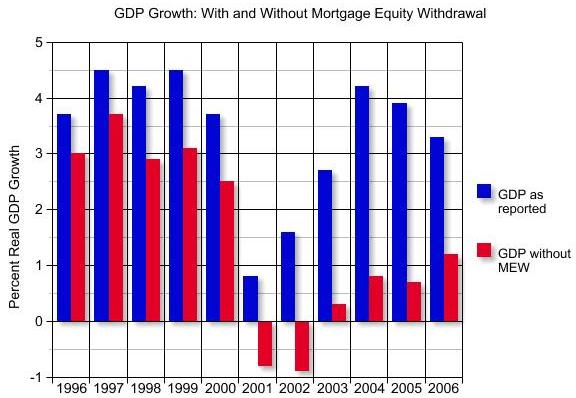

What was the impact of MEW on the economy? It was absolutely essential to the expansion. Without it, the economy would have been expanding at a 1% rate - or worse. The psychological impact of this anemic growth could very likely have caused that double-dip recession the Fed had feared.

Consider the following chart of annual GDP. It is calculated with and without MEW, using data from the Federal Reserve. The amount of MEW is calculated via the Greenspan-Kennedy method (Note that the statistical system developed by Fed economist James Kennedy and former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan is not officially recognized by the Fed).

Using Greenspan's estimate of approximately 50% of MEW flowing through to personal consumption, it is possible to estimate the impact of MEW on GDP. As the chart below shows, the impact on the economy has been nothing short of breathtaking. Since rates hit their lows in 2003, Mortgage Equity Withdrawal has been responsible for more than 75% of GDP growth:

This is a radical change from prior periods. In the second half of the 1990s, equity extraction was good for "only" about 25% of GDP growth (plus or minus). In the current cycle, it is three times that.

And, it is falling. As rates have ticked up, two things have happened: equity extraction has trended downwards; it had fallen to $113.5 billion in Q3 2006. This is off by ~50% from the 2004/05 peaks. It is no surprise that GDP has trended downwards along with MEW.

Slowing Housing Market and the Economy

To review our story so far, a post-crash, post-recession economy was non-responsive to the usual economic stimuli. Despite everything the government threw at it, the economy remained moribund. It took the Federal Reserve slashing rates to levels not seen in nearly half a century - and then leaving them for a year - before the economy actually showed signs of life and responded.

And oh, how it responded. Real Estate boomed, automobile sales spiked, commodities exploded, oil broke out to new record highs. The old inflation standby, gold, reached levels not seen in decades. Industrial metals reached all time highs. Corporate profitability, as a percentage of GDP, reached never before seen heights.

Despite all this, salaries remained flat. But mortgage equity withdrawals allowed the consumer to keep on spending, even as their savings rate went negative and their Compensation as a percentage of GDP dropped to multi-decade lows.

Alas, all good things must come to an end, and now, the trade is now unwinding. The decline in Housing has been well documented, and despite some recent signs of stabilization, it doesn't appear to be anywhere near a bottom. Housing starts have plummeted, and inventory remains at extremely elevated levels.

And, if mortgage applications and building permits are anything to judge by, this trend is likely to persist for some time into the future. Mortgage originations volume has decreased 16 percent in the first half of 2006, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association's. Home refinancings have cooled also.

And, we may be early in the Housing downturn in terms of duration. According to research from Goldman Sachs, over the past three cyclical declines since 1960, new home unit sales have dropped on average by over 50% over a 26-53 month period. The statistical top in housing activity was only 15 months ago; housing starts are off by only 20%. From this historical perspective, we could still be very early in the downturn. We still are near 15-year highs in terms of existing home inventory.

Where does that leave us? With elevated levels of inflation - off its peak but still worrisome. At the same time, economic activity is slowing. This has the Federal Reserve somewhat boxed in: The Fed closely follows core inflation, and it remains at "uncomfortable" levels. Yet growth is clearly decelerating.

Many observers are hoping that the housing slow down will remain "compartmentalized," and will not have an impact on other sectors. We find this difficult to imagine. Indeed, we already see significant evidence to the contrary.

Symmetry is why. The positives from the residential real estate boom have had an enormous net impact on growth during Housing's boom. We have detailed above the primary gains accrued to the economy thanks to the increases in real estate related employment and consumer spending.

We have yet to see a persuasive case as to why the absence of these benefits won't have a negative impact as housing cools. We simply do not believe you can have it both ways (although that hasn't stopped some commentators from trying). Not unlike energy, which apparently did not contribute to inflation as prices rose, but was a huge force for a decrease in inflation as prices fell. Those sorts of asymmetrical arguments fail to be intellectually satisfying.

The Canaries in the Coal Mine

It is apparent that Housing is cooling and the economy is decelerating. What are the indicators that can warn us that a hard landing is forthcoming? Consider the following elements:

Transportation companies are the early warnings for consumer spending. In Q4 of 2006, many of the Transports have announced declining shipping volumes and decreased their outlooks for 2007. When firms such as Federal Express, UPS, Yellow RoadWay - the leaders of the industry - say they see problems coming, we pay attention. Note also that the American Trucking Associations' for-hire Truck Tonnage Index plunged 3.6 percent in November, following a 1.9 percent drop in October. The index has decreased 8.8 percent compared with a year earlier, marking the largest year-over-year decrease since the last recession.

Holiday Retail Sales slipped below expectations. It's not just retailing giant Wal-Mart. Discounters, electronic stores, department stores, and mall based retailers delivered a holiday shopping season that was described as disappointing and lackluster. According to MasterCard Analytics (based on cash, check and MC purchases), holiday sales increased only 3% this year. That's the weakest since 2002. And with inflation running about 3%, this means that Real Retail Sales (after-inflation) were flat year over year.

Durable Goods have also been on a downswing. Durable goods orders fell by 1.1% in November, according to a Commerce Department report. It was the second consecutive monthly drop in durables orders excluding transportation, and the fourth decline in the last five months.

Manufacturing Indices have shown weakness accelerating: ISM manufacturing index slipped below 50 (to 49.5) for the latest reporting period of November. Data below 50 reflects contraction. While some economists are looking for a recovery in December, the data coming out of the regional Feds implies further deceleration.

Mortgage Foreclosures have been accelerating, especially in the sub-prime areas. While not yet at record levels, we see no signs that foreclosures are slowing down. Indeed, as the interest-only and variable mortgages issued in 2003 and 2004 "reset," we would expect to see foreclosures accelerate.

Automobile Sales have been also pointing towards a hard landing: The "dealer doldrums indicator" suggests that the economy is cooling rapidly. Considering how many autos were paid for or financed out of home equity, this should come as no surprise. In previous cycles, this measure (a rolling 12 month rate of change in sales by new-car dealers) has a good track record forecasting recessions.

Business CapEx spending has slowed: Business investment in new equipment and software fell in Q2 for the first time since the recovery began. Many of the forecasts of a soft landing / Goldilocks scenario call for business spending to pick up as the consumer begins to slow. So far, we see little evidence of this happening.

Transports, Retail sales, Durable Goods, Manufacturing, Foreclosures, Autos, Business Capex: It reads like a laundry list of the most significant sectors of the US economy. All of these early indicators are flashing danger.

Indeed, just as these warning signals are lighting up, we cannot help but note that corporate profits are at record cyclical highs - just as consumer spending has begun to soften.

With the S&P500 trading at a P/E of about 17, the market is fairly valued. In the event that any of these issues worsens, we cannot imagine how corporate revenue and profits won't be impacted in a negative way. Any appreciable spending slowdown by either consumers or business will not bode well for equities. Even a modest fall in revenues could make stocks suddenly look very expensive. That's what typically occurs at the end of cycles: What once looked reasonably priced suddenly becomes expensive.

Conclusion

Supply Side economists are fond of crediting the 2003 tax cut package for the economic expansion of the past 3 years (somehow, the 2001 tax package gets overlooked). We simply disagree. While we enjoy tax cuts as much as the next fellow (Damn AMT!), the data strongly suggests that it has been low interest rates and a booming Real Estate market - not tax cuts - that deserve most of the credit for driving this expansion. Indeed, by nearly every measure, this recovery makes us wonder what the Supply Siders are bragging about.

What they can hang their hats on is the rally off the summer lows that has driven indices like the Dow to record highs. However, markets are fickle things. We are quite fond of the saying "Beware of economists looking for validation from short-term equity moves."

Credit or blame for this economy lie mostly with the Federal Reserve. It has been 6 years since the last recession began. At this point in the business cycle, the Fed seems to be running out of maneuvering room. Unless inflation decelerates rapidly (allowing more rate cuts), or the economy somehow manages to re-accelerate without igniting more inflation, we find it hard to imagine how the economy avoids a hard landing. In a post-crash economy, that's about the best we can hope for.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.