|

The End of Complacency?

This week we look at the recent upspike in volatility, see if we can connect some dots with the recent slew of earnings downgrades and the problems in the subprime mortgage world, and follow the money as risk is being taken off the table. I don't "buy" the China problem, but there may be an Asian connection. Let's try and keep it simple as we try and see what's behind curtain #3 labeled "Which direction is the stock market headed?"

Volatility? What Volatility?

Let's see if we can put last Tuesday's 400-point drop in the Dow into perspective. Good friend Barry Ritholtz wrote the next day:

"This was the longest period - nearly 4 years - we had gone without a one-day 2% correction in the Dow in market history. 416 point drops seem pretty big; however, it may have been the 8th largest point drop, but it was only the 237th largest percentage decline since 1900."

Hard to get too excited about something that doesn't even make it into the top 200. But let's look at this note:

"From 1916 to 2003," Benoit Mandelbrot writes in The Misbehaviour of Markets, "the daily index movements of the Dow Jones Industrial Average do not spread out on graph paper like a simple bell curve. The far edges flare too high: too many big changes. Theory suggests over that time, there should be fifty-eight days when the Dow moved more than 3.4 percent; in fact, there were 1,001. Theory predicts six days of index swings beyond 4.5 percent; in fact there were 366. And index swings of more than 7 percent should come once every 300,000 years; in fact, the twentieth century saw forty-eight such days. Truly, a calamitous era that insists on flaunting all predictions. Or, perhaps, our assumptions are wrong."

It is only in the context of the last few years that such a market move could be considered truly unusual. Consider that the 7% move that Mandelbrot mentions would be about 840 points on the Dow. Now THAT is volatility!

Barry goes on to show how in the last three onsets of a large market drop, they were followed by increased volatility both to the upside and downside. Looking back on 1997, 1998, and 2000, from the initial drop in the market we saw multiple double-digit moves up and down in the immediate months following. Take 2000:

"In December 1999 and January 2000, several 3% down days were registered. The market peaked on March 10, and two days later suffered a 6% drop (peak-to-trough intraday). The next day was just under a 4% whack.

"These moves set up what would turn out to be one of the wildest years in market history: From that March peak to the beginning of April, the NASDAQ dropped 29%. A 22% bounce by April 10 was followed by a 27% drop, a 23% gain, and a 23% sell off - all before May was over!

"From the lows in May, the NASDAQ subsequently rallied 41% by mid-July. Between then and September 1, the Nazz dropped 17.9% and rallied 21.0%. From September to December, the NASDAQ markets then dropped over 40%, to just about 2,300."

In short, it would not be unusual for there to be even more volatility in the future, in BOTH directions, as the bulls and bears battle it out. In fact, we should expect it. If we do get a 8-10% correction, look for the sell side to start talking about how the economy is doing fine and the correction is now ready to be over. And look for a new bull run. I think it will fall short, and more volatility to the downside will ensue? Why? The fundamentals.

The Fundamentals of Earnings

I wrote about this a few months ago, but it bears (pardon the pun) repeating. If you go to Standard and Poors projected 2007 earnings, you will find that they project that "as reported" earnings for the S&P 500 for the last two quarters of 2007 will be LESS than the earnings in 2006, after healthy gains for the first half. Of course, the subject-to-manipulation operating earnings (what I call EBIH or Earnings Before Interest and Hype) are still projected with healthy increases.

(The link is at: http://www2.standardandpoors.com/spf/xls/index/SP500EPSEST.XLS)

We have seen earnings estimates come down this quarter. That should not surprise us, as the economy was slowing down somewhat. But a slowing economy is not a necessary precondition for earnings to fall.

I was stuck in traffic yesterday afternoon and got a call from good friend and area neighbor Ed Easterling, who was also stuck in traffic, so it gave us some time to mull over the markets. The conversation drifted to earnings.

Ed comes up with the greatest statistics. Did you know that there have been 17 times in the last century where earnings have dropped but the economy was growing? His point was that there is a business cycle and then there is an economic cycle, and the connection between them is not as straightforward as one would think.

Who Repealed the Business Cycle?

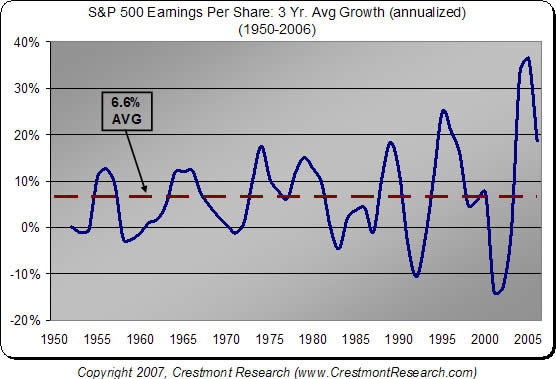

Earnings for the corporate world as a whole cannot really grow faster than the economy as a whole, or basically GDP plus inflation. There is a business cycle and an earnings cycle. Earnings on a three-year average-growth basis average about 6.6%. Earnings growth seems to fluctuate around that median. Looking at the following chart, we can see that the recent growth in earnings has been the strongest in the last 56 years, although it's starting to come down.

But we are still at almost three times the level of the average. If we are going to "revert to the mean" then we will need to see earnings growth come down a whole lot more, and possibly even decline. Is there any reason to think that we would?

Students of economic history would suggest so. Unless we have repealed the business cycle, the current run of five straight years of earnings growth is quite long. In fact, if earnings grow in 2007, it would be equal to the longest run of the last century. Let's look at the next chart. Notice that not only is the current run quite long, it is also the strongest by a wide margin, although it is coming off the largest drop (50%!) in earnings in history in 2001, so there was a low base. If earnings had dropped a "mere" 25%, then the current run would be more in line. For a mild recession, corporations sure got hit.

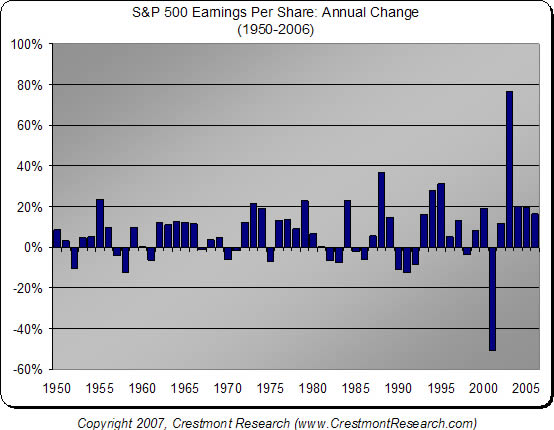

One last chart from Ed. Look at the annual change in earnings from 1950. Notice that there are periods where earnings actually decline. These are NOT necessarily contiguous with recessions, although all recessions do produce earnings decreases. So it is not necessary for there to be a recession for us to see a drop in corporate earnings. Historically, earnings have been an average of 9% of GDP. Today they are at 12%, higher than at any period for the last 50 years. We would expect that percentage to revert to the mean. That can happen two ways. Either earnings growth slows over a long period of time, or earnings drop, perhaps due to a recession.

But is there anything on the horizon that would suggest that earnings growth will not only slow but actually fall? (By the way, S&P projects very robust earnings growth for 2008, which admittedly is a long way off.) I think there is.

The House of Subprime Blues

They are opening a House of Blues in Dallas in May, and Dan Akroyd and Jim Belushi are kicking it off. I want two of those tickets, and am having a problem getting them. But I do not want a ticket, except on the short side, to the House of Subprime Blues. It seems every week we are greeted with the story of yet another subprime mortgage firm biting the dust. I was talking with Dr. Gary Shilling this afternoon, and of course the topic of subprime lending comes up. He told me of a web site that tracks the woes of subprime mortgage firms, at www.lenderimplode.com, which he said shows that 27 subprime mortgage lenders have gone belly up. I looked, and it is now 28.

One Aaron Krowne operates the site, and it is full of links about the woes of subprime and Alt-A mortgage firms. (Interestingly, Google has populated it with a lot of ads for mortgages.) Six of the top 25 subprime firms have closed their doors, and more are under very clear pressure.

And it is going to get worse. Freddie Mac this week put the mortgage banks on record that it will stop taking no-document and other riskier loans, which were the staple of the business.

My sources tell me that there may not be one independent subprime mortgage firm within a year or so, all of them having been forced to either close, merge, or sell. They are having to take back the mortgages they sold that are now going into default, and they simply do not have the capital. We are on the front end of the wave of foreclosures.

I have written that up to 20% of subprime mortgages written in the last two years are expected to go into foreclosure. Already we have a delinquency rate of 10.5%. But now we are seeing pressure on what are known as Alt-A loans. These are loans which are made to borrowers with better credit scores, but still not quite ready for prime. The Alt-A segment counted for 16% of the market, and the subprime counted for 24% last year.

Many of the Alt-A mortgages were also of the undocumented variety. Now, the creditworthiness of these loans is better, but Fitch Ratings suggests there is still a significant number which could go into default, estimating that it will "only" be 10-20% of the subprime problem. That could mean a default rate of as much as 4%.

There are two problems here. One is that a lot of homes are going to come back onto the market over the next 12 months, when there is already a 7.8-month supply of homes for sale. This is going to depress house prices.

Secondly, we are seeing banks beginning to raise the lending standards, as they should. This chart from Gary Shilling shows that bank credit standards as a percentage of banks which are tightening standards are the highest since the early '90s, and they are just going to get higher. As an example, Impac Mortgage Holdings, an Alt-A lender, has tightened its lending standards 17 times over the last year.

Open up your Bloomberg page this afternoon. Look at the headlines. The Fed says the "subprime mortgage market needs closer scrutiny as defaults rise." "Fremont Quits Subprime Market." "Criminal Accounting Probe" on another lender. You can bet that standards are going to get a whole lot tighter. And that is not a bad thing. Banks should not be in the business of making bad loans.

Shilling and I did a back-of-the-napkin estimate of the impact on the housing markets of the increased standards, coupled with the demise of interest-only and teaser-rate loans. It is highly likely that the buyers of 10% of the homes that were sold in the last two years would not have qualified to buy those houses, and it is possible it could be 15% or more. That would have probably taken a lot of the irrational exuberance from the housing market, and avoided the bubble and the aftermath. I know there are those who blame it on Greenspan and his creation of cheap money. I don't buy that. He aided and abetted, maybe. But it was sloppy lending practices that were just as much or more to blame.

If you take 10-15% of the potential buyers from the market going forward, that is a serious problem, especially as you are adding homes to the market from foreclosures. The notion that we saw a bottoming of the housing market in January is ludicrous. Housing bottoms take years to accomplish, not a few quarters.

The top of home prices was in October of 2005. Borrowers who are trying to refinance their mortgages are going to come under increased pressure in many markets, as home values slide below their loan values. They may be stuck with their high adjustable-rate mortgages or lose their homes.

Look for increased calls from Congress for rules which require lenders to assist delinquent borrowers who are caught in the trap of an adjustable-rate mortgage. The banks who hold these mortgages are going to be characterized as "predatory" and will garner no sympathy, although their shareholders might have a different view.

Home prices are going to come under increased pressure. The "wealth effect" we had from rising home values is going to go away, and we could even see a negative "wealth effect," as families which were counting on 15% appreciation to build up savings now have to do it the old-fashioned way.

I think we are going to see an actual slowdown in consumer spending as the year goes on, in spite of the solid increases in income we have seen the past few quarters. And that is the stuff that makes for lower corporate earnings. And that leads to earnings disappointments, which could be the catalyst for continued volatility to the downside.

By the way, bank loan loss reserves are at their lowest levels in at least 16 years. In the last few days, we are seeing credit default swaps of the major investment banks being pushed to only two levels above junk status. That is overblown, but it shows the distress when their own traders push their credit insurance to such low levels. (Don't you love the irony?)

We are seeing credit spreads widen. While the moves are significant, we are nowhere near back to "normal." There is a lot of room on the downside. Investors are taking risk off the table, or demanding more returns for their risk capital.

Bear Stearns's stake in non-investment-grade retained mortgage securities, or what its keeps from packaging loans into bonds, represents about 13% of the firm's "tangible" equity, according to CreditSights.

For Lehman, it's 11%. Goldman, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill don't disclose how much of their total retained securities are rated below investment grade, or junk. Overall, their exposure is in "the low to mid teens," CreditSights said.

The major investment banks have made a great deal of money over the past few years from securitizing subprime mortgages. That portion of their income is going to drop dramatically.

I should note, these banks are not in any trouble. Goldman, Merrill, and Morgan Stanley made a combined and record $24.5 billion last year. I am merely suggesting it is going to be harder for them to set another record this year.

And one final and quick note. I don't buy the link to China as the cause of Tuesday's drop. But I am suspicious about Japan, as the yen carry trade is clearly unwinding, and that is taking liquidity off the table. How much? No one knows, and there is still a lot of capital. But the carry trade was trading capital, and that always shows up on the margins. No smoking gun, but it is an interesting coincidence.

The End of Complacency?

The stock markets had their worst week in four years, and are at a three-month low. Bonds had their best week in five months. Trading in Credit Default Swaps (basically loan insurance) jumped big-time, as did prices, as lenders are starting to worry about their portfolios. All in all, a little volatility came back into the market, and complacency may be looking for an exit door. But that should not have been a surprise. Complacent investors and businesses nearly always get hammered.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|