|

China and the Hedge Fund Dragon

This week we look at the possible latest entry into the hedge fund world, The People's Republic of China; review the cockroach principle of subprime mortgages; and investigate the possibility of whether we need more derivatives and not less than the $283 trillion or so we now have. It's a lot to cover, but it should all be interesting.

China and the Hedge Fund Dragon

And speaking of China, we all read the stories about the rapid growth of the economy, the increasing percentage of the growth in demand for commodities and energy that comes because of that growth, the increased trade deficit with the US, and the rapid increase in foreign reserves. China today has over $1 trillion in foreign reserves, much of it invested in low-yielding US bonds. This has served to keep US interest rates low and allow American consumers to borrow at cheap rates and not coincidentally buy a mountain of Chinese products.

These reserves have mostly been managed in a benign fashion. But some recent speeches by high-level Chinese leaders suggest that period may be coming to an end. In a report this week from my friends at Stratfor, we read that:

"The vice chairman of China's National People's Congress, Cheng Siwei, said March 8 that the Chinese government needs to put some of its mammoth $1 trillion (as of Jan. 1) in currency reserves to better use. Cheng said he broadly agrees with International Monetary Fund assessments that China needs to keep 'only' about $650 billion as reserves, and should apply the remaining amount to more efficient purposes. While Cheng is not ultimately the decision-maker for the reserves, his statements are just the latest in a series of leaks that point to an imminent change in the way Beijing manages its currency reserves. Whatever decision Beijing makes, it will shake the world."

There are precedents for more efficient management of reserves by governments. Singapore invests its reserves in stocks and bonds, as well as the outright owning of a wide variety of businesses. Norway has US$289 billion in stocks and bonds under management in its Government Pension Fund. (Note that Norway only has about 4.6 million people.) The fund can invest up to 50% of its assets on the international stock market.

It makes sense from a Chinese point of view to try and get a better return on its assets than US treasuries, especially given the fact that over time the dollar is going to depreciate against the Renminbi. The Chinese allowed their currency to start floating within a specified band in the summer of 2005. After an initial drop of a few percent, the dollar has slowly moved down since that time. If you are only getting a 5% yield on your US bonds and giving up 3% on currency depreciation for a net 2%, that is not a strong argument for continued investment in the dollar.

U.S. Dollar to Chinese Yuan Exchange Rate

$650 billion is a strong reserve cushion that would allow the Chinese to be more creative and long-term in their management. They would not need to necessarily only invest in liquid investments. As an example, the total foreign investment in all of Africa in 2006 was only $38 billion. China could easily increase that number by investing in oil projects, farmland, mining, and other infrastructure projects that would guarantee it sources for the materials, commodities, and food that a growing economy is going to need.

But $350 billion is just the beginning. China is adding at least another $100 billion each year. How do you put that to work? Of course, you continue to invest in your own economy, but China is going to need a lot of material and food in the coming years. They will not only compete for resources with the slower growing economies of the US, Europe, and Japan, but with the rapidly growing economies of the developing world and especially Asia.

What if China takes half its growth in foreign reserves and puts it to work? You could be talking US$1 trillion by the end of the next decade. That is a massive amount of investments. As Stratfor notes, that will make a mighty big splash in the pond; but as yet, no one knows where the splash will be. It is just speculation as to where.

But just as it is logical for individuals to plan for their future, it is also logical for governments to do so. Anyone with an Excel spreadsheet can predict the demand for materials and food for the total world at current growth levels. While I am a believer that the free market will find a way to supply that demand (of course, price is the issue), a reliable supply of energy, commodities, and food will be an increasing focus of attention on the part of many world governments. China's huge reserves offer it a way to secure that supply line in a way not afforded to many nations. I see no reason for them not to use it. I would if I were them.

Of course, that has ramifications for the rest of the world. I would not expect China to move all at once, as that is not the Chinese way. But over time the results could be significant.

As an aside, there is a lot of breathless speculation about the Chinese moving a significantly larger portion of their reserves into euros. If I was the European Central Bank, I would want to discourage that. Since the Renminbi and the US dollar are more or less linked, a significant move into euros would strengthen the euro against both currencies, increasing the US and Chinese export advantage.

It seems to me that it makes more sense, from a Chinese viewpoint, to put spare reserves into higher-producing assets than US or euro bonds. China may be about to start down the path to becoming the world's largest private-equity hedge fund.

To put that into perspective, at an Akin-Gump seminar on hedge funds I attended yesterday, one speaker asserted that we will soon see a deal for a single $50 billion private-equity fund. Combine that with leverage and you could see a fund with $200 billion of buying power. And that is just one fund! There are many others likely to be funded in "lesser" amounts as well. So China's $350 billion is big, but there are also a lot of very big "beasts" that will be vying with the Chinese dragon for opportunity.

And since we are talking about very large numbers, let's stop using billions and go to trillions. As in $283 trillion.

The Need for More Derivatives

Look at the following two charts which show the growth in derivatives over the last 20 years, sent to me by Ray Lombardo of UBS in Newport Beach, California. The data is from an ISDA market survey and the International Monetary Fund GDP. You can see the explosive growth. Note that there are now 6 times the amount of derivatives as the total world GDP. Isn't that a bubble? What would happen if it pops?

Ray helpfully sent me the underlying data as well. The vast majority and the source of the growth in derivatives are interest-rate and currency derivatives, currently at $250 trillion. There is $26 trillion in credit-default and $6 trillion in equity derivatives.

A derivative is a financial contract whose value is based on, or "derived" from, a traditional security (such as a stock or bond), an asset (such as a commodity), or a market index. Derivative instruments are contracts such as options and futures whose price is derived from the price of an underlying financial asset.

Just as you buy insurance on your house or health, derivatives can be a form of insurance. If you are a farmer, you want to know what the price of corn is going to be a year from now, so you can lock in the price. If you make cereals, you want to know what your costs are going to be, so you lock in your price. Speculators come in and provide liquidity for the natural hedgers.

If you are an international company, you want to hedge out your currency risk. If you lend money, you want to buy insurance (credit default swaps) on your portfolio. You sell options on your stocks, or buy options to provide more leverage on a possible move up. You can hedge against a drop in the market. Many mutual funds are nothing more than derivative portfolios.

One of the more important books that you can read is Peter Bernstein's Against the Gods - The Remarkable Story of Risk. In it he details how humankind developed concepts of risk. The odds on dice weren't even known until the Middle Ages. Lloyds came along in the 1600s and allowed merchants to hedge the considerable risks of financing a trading ship.

Insurance and hedging are at the heart of the global marketplace and the collective growth in the world economy. And derivatives are another form of insurance. Yes, there is a great deal of speculation, but that provides liquidity and over time lowers the cost of such insurance, although at certain inflection points it can wildly skew the prices.

I was having a conversation with Dr. Woody Brock last week. He has given me permission to use his essay on why we need more derivatives and not less. It will be a future Outside the Box. We talked about the risk of a blowup. One of his concerns is not the systemic risk that comes from the large users of derivatives, as authorities in extreme cases can move to stem the problems, as in the Long Term Capital Crisis.

What if the risk is not from major players but from smaller users that are harder to identify and deal with? I will let his essay outline his thinking in a few weeks, but the point is that the true systemic risks of the growth in derivatives may not come from the sources that we are currently concerned about, hedge funds and large investment banks.

Yes, if your fund or bank loses money, you as an individual investor are not happy, but that is the market risk you take. Look at the major hits the market has taken and didn't even slow down or look back. Refco? Amaranth? It is precisely the dispersal of risks among more and more individuals, funds, and banks that helps cushion the system.

Cockroach Principle and the Subprime Mortgage Market

The Cockroach Principle says there is never just one cockroach. If you see one running across the room, that means there are many more in the walls and behind the counters. I have been highlighting the problems in the subprime space for a long time. As I wrote months ago, this is going to be a major scandal. It is the main (and almost only) reason that I think we are going to have a recession in the US.

Last week www.lenderimplode.com listed 28 subprime mortgage firms that were shut down or taken over. The count is now 34. Yesterday the third largest lender of subprime mortgages, New Century, stopped accepting new loan applications. The shares were once at $50. Now they are under $4 and falling. The Financial Times reports that they cannot meet their margin calls from their lenders.

Essentially, New Century has been shut out of the capital markets. They are being hit with a wave of lenders who are demanding they take back the mortgages they sold, and my guess is that they do not have the capital they need. Maybe they can sell assets and get them. Who would take their paper or their mortgages today, knowing the problems? The money available to subprime lenders is rapidly evaporating, and until the lending standards are tightened considerably, it will remain that way. Many of the buyers of the Mortgage Backed Securities are going to lose some money.

Option One is an Irvine, California-based subprime lender. Yesterday they stopped doing 100% loans on the value of a home. CEO Steve Nadon pointed to an increase in loan submissions as a result of many of the company's competitors running into funding problems.

"We are getting a lot of 80/20s and 100% CLTV deals that used to go to our competitors," the letter said. "While there is nothing inherently wrong with those types of loans from a pure credit standpoint, right now they have a fundamental flaw that we simply cannot overcome. That is the almost complete lack of appetite for the product by the bond market... To originate a loan product that no investor, in today's market, wants to buy is irresponsible."

Consider even a lender like Countrywide which only had about 10% of its portfolio in subprime. They can probably weather the storm, as their main business is prime mortgages. But the founder and CEO, Angelo Mozilla, has sold $140 million of his personal holdings, and almost $600 million of insider stock at Countrywide has been sold in the past two years.

I have highlighted this problem before, so will not go into it in detail again. Subprime mortgages are pooled and divided into different risk tranches, with the most risky being the "equity" portion of the pools, typically about 4%, and these equity portions are again put into pools with 80% of these equity portions now getting investment-grade ratings. These latter pools are going to lose money, if not go bust outright. The rating agencies are going to have major heartburn over this failure to adequately see the risks. Cue the lawyers, stage right.

The following note is from good friend Dennis Gartman (The Gartman Letter). He could not reveal his source or vouch for the accuracy of the story, but it is like other anecdotal stories I read.

Let's say you have a good credit history. You pay your bills and get a nice credit score. But let Dennis tell the story:

"However, in the past several years, mortgages were made to people who should never have gotten one. Homes were built for people who could not afford them. Decisions were made that shall prove to be utterly ill advised and in some instances almost evil in intent, and were it not so sad, some of these loans would be comical in nature. Some are already going bad. These are the first 'cockroaches.' More shall... indeed many, many more shall. These are the other 'cockroaches' hidden now from view, but which shall come sadly to view over the next many months.

"Thus we note for our clients a piece sent to us by one of our readers yesterday which may or may not be factual, but which tells the story of what has happened in the mortgage business in recent months, and which tells us what is about to happen. With that in mind, please read on:

"A 'customer' bought his house in '05 for $650,000. The house was new and he blatantly over-paid. He put no money down and the builder paid his closing costs. Just so we're clear, he didn't bring one red cent to the deal at any point. He got a no-doc loan. Just so we're clear about what no-doc is, he didn't even fill out the income or asset sections of the 1003. This man didn't lie about how much he made or had. He simply made no representations on the subject. He had 'perfect' credit. Just so we're clear, 'perfect' credit in this case consisted of +24 months of clean payments on two credit cards with high limits of $3K and $4K.

"There is no consideration about how much credit he could or had been able to handle. He received 80/20 financing. The 80% first is a negative amortization loan. Today he wants to get a fixed-rate loan to pay down principal. The problems: He made the minimum payments on his negative amortization first. He now owes +$37K more than he originally did. On top of the fact that he overpaid, the house hasn't appreciated. He probably owes in the neighborhood of $100K more than the house is worth (and that's before estimating any negative impact on price if he goes to foreclosure), and 37 houses are for sale in his immediate neighborhood. The big punch line? He is a 26-year-old, single busboy for a catering firm. He makes $33K per year.

"Heaven help us!!!! What more really can we say, other than 'What's your bid for this busboy's house?' Our bid is something south of $300K, and we are not all that certain that we'd make that bid stand for more than a day, fearful of being hit... fiscally and physically... by the busboy.... AND the lender."

The lower end of the housing market is going to find a dearth of buyers, as they will not get financing and a lot of homes are coming back onto the market. It is going to be very hard to get a floating-rate mortgage turned into a fixed-rate mortgage, and consumers are going to see their payments soar. Foreclosures area at an all-time high and rising. Cue the congressional hearings, stage left.

A special advisory committee of the Federal Reserve warned Thursday of a rise in the number of foreclosures, as new guidelines were issued. Subprime mortgages, about 20% of the total market, were 50% of the foreclosures last year. That is set to rise this year.

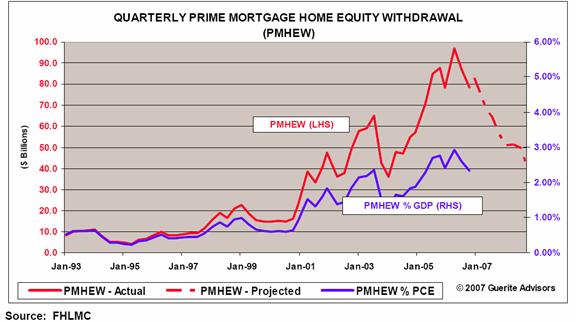

As the problem spreads, it is going to hit home values and that is going to limit the amount of money that can be borrowed by consumers as Mortgage Equity Withdrawals. It is not just a problem with subprime mortgages, it is starting to hit the prime mortgage world. Indeed, friend Hugh Moore at Guerite Research writes today about what he calls Prime Mortage Home Equity Withdrawals (PMHEW):

"Based on data from FHLMC (Freddie Mac), PMHEW grew from an average 0.55% of GDP between 1993 and 2000 to an average 1.93% between 2001 and 2006. It reached an astonishing 2.93% of GDP in the second quarter of 2006. However, Freddie Mac is projecting that PMHEW will decline 20% in 2007 and an additional 30% in 2008; 43% below 2006 levels. Such a drop could reduce GDP by 1% to 2% over a two-year period of time. The decline in PMHEW is due to the fact that the mortgages most likely to be refinanced in 2007, 2008 (and 2009) were originated in 2004 and 2005 and housing prices have appreciated little since then. In short, those homeowners most likely to refinance are running out of excess equity."

Look at the chart which shows that Freddie Mac expects MEW to drop by over 50%. And that is on today's home valuations:

In short, consumer spending is going to take a hit. How much? No one knows, but this is a problem that is not in the index of leading economic indicators. Will it be enough to send the US into a mild recession? I still think so. We will see.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|