|

Blame It On Stability

This week we look at length at an outstanding new book just hitting the bookstores by good friend Paul McCulley (of Pimco fame), called Your Financial Edge . The main themes will give me an opportunity to weave in a few thoughts about some recent data, and a lengthy telephone interview with Paul, done just before writing this week's letter, will bring us up to date on his current thinking. I think readers will take away a few good ideas, so let's jump right in.

Paul McCulley is someone we should listen to. He not only runs a rather large portfolio at PIMCO, his calls on the Fed are critical. In just one day, a correct prediction by McCulley that the Fed will unexpectedly raise or lower its Fed funds rate by a quarter of a percentage point can mean a $3-5 billion jump in the value of the $670 billion worth of mutual funds and private client funds managed by PIMCO. He writes a monthly column that I consider a must read, and his writing has been a feature in Outside the Box more than that of any other analyst. He is simply one of the best financial minds in the country. When he talks, you should listen.

Your Financial Edge was co-written with Jonathon Fuerbringer, a reporter for 24 years with the New York Times, who brings a very clear, crisp, and fast-paced style to the book; but long-time fans and readers of Paul recognize the source for the driving themes of the book. The book is subtitled "How to Take the Curves in Shifting Financial Markets and Keep Your Portfolio on Track" and is a marvel in how it simplifies the problems facing investors in the coming years, giving us a framework for both understanding and dealing with them. This book should be read by both investors just starting out and seasoned pros, and both will come away with a lot of new ideas and understanding of how the market works. I really can't recommend this book highly enough, and if you read it you will see why I think it deserves at least a full letter on its own.

This is not just a book on economics. It is a practical book, giving you a view into how Paul would specifically allocate investments in both short-term and long-term portfolios that he personally manages. For a bond guy, he has more tolerance for risk than you might think, and that is for a reason he outlines in the very first chapter. (Quotes are from the book, except where noted.)

Blame It on Stability

Paul starts out with the primary problem facing most investors: returns on most asset classes are lower and lower, and the prospects for a return to the levels of reward that we saw in the '90s are slim. Long-term interest rates are where they were when the Fed started the last round of rate increases. The spread between bonds of all classes and US bonds is at its lowest level ever (except for sub-prime bonds, but who wants those today? - maybe at some point as a distressed play). Valuations on most stocks are at levels which historically have suggested lower than average long-term returns. Energy is not cheap. Neither are commodities or real estate. There are not as many pockets of value in the world as there were 25 years ago.

"In other words, we are in the midst of a risk squeeze, where investors will get less for more risk. So it is likely that many investors, in order to meet their investment and savings goals, will have to take on what is now considered above-average risk just to get an average return, or substantial risk to get an above-average return.

"The most cautious investors, whether they like it or not, will not have the luxury of putting much of their money into the traditional safe harbor of the Treasury market and earning enough to live on."

Let's blame it on stability. "The reason investors have to get to know risk better, despite the potential discomfort, is that we got what we wished for--an economy with inflation in check."

The battle against inflation started in 1979 with Volcker and has been more or less won, notwithstanding the recent small (relatively speaking) bout of inflation. As Paul noted in our conversation, and as I have written, the next recession will once again bring deflationary concerns. And it is this relative stability that has given investors a sense of confidence to bid up prices in all sorts of asset classes. But that is a one-time event. We don't get to travel that road again, unless we return to a period of instability, which would not be good for prices.

"There is a difference between going to financial heaven and living there. During the journey there is a suspension of the historical relationship between stock prices and earnings that allows equities to generate extraordinary returns. It's akin to suspending the speed limit on an interstate highway. But once the journey is over, stock prices and earnings return to their historical relationship and the expected return for stocks, like the speed limit, falls.

"To put it another way, total returns for stocks over the past two decades are irrelevant in considering the merits of stocks for the next two decades."

Paul then proceeds to talk about diversification and areas where investors can increase their risk. He likes to look abroad, both in the developed and emerging markets. Paul is generally bearish on the dollar, so that gives international investors a little wind in their sails, while also adding some diversification. But he does note that there is a rising correlation between international markets and the US markets, so that in times of market volatility the promise of diversification may not be as great as in the '80s or '90s.

The first two chapters are great for investors looking for guidance on general portfolio construction, but Chapter 3 is a must read for everyone. Entitled "What Can Go Wrong?", in it Paul lists several areas which are threats to the markets in general. While he acknowledges there are exogenous threats (problems coming from outside the economic sphere) like terrorism, disruptions in the oil supply, and so on, he focuses on five areas of concern which are likely to crop up in the future: the US trade deficit, the US budget deficit, market bubbles, recessions, and China. Let's look briefly at each and then at a connection I see among all of them.

That Day of Reckoning

The first of his concerns is the current account deficit or trade deficit.

"But the argument that the current account deficit is unsustainable in the long run is irrefutable... That day of reckoning, when it comes, will shake up the U.S. economy in all the wrong ways, with a falling dollar, rising interest rates, and rising inflation. The biggest worry is that the current account deficit could create a crisis, where all of these things happen quickly. For investors, that would be a nightmare, with stocks, bonds, and the dollar all down sharply at the same time, the economy in a slump, and no place for investors to hide.

"...That argument is right in the long term. But the long term is the wrong view to take of the current account problem. We are all dead in the long run, as John Maynard Keynes said, so sustainability is not the right issue. The real argument about the current account deficit from an investor's point of view is how long the unsustainable can be sustained. Or to return to Keynes, what happens before we die? The answer is that we live, or in the case of the current account, that it is sustainable in the medium term.

"But while that means the worst can be put off for a while--maybe long enough to get the current account deficit under control--the current account deficit will still have its fallout, and that is not going to be pleasant. Inflation and interest rates will be higher than otherwise would be the case and there is a chance of an error. The then troublesome current account deficit was a player in the background of the squabbling among the United States and other nations that was followed by the 1987 stock market crash.

"There are several reasons, however, why a current account crisis is not around the corner and why this deficit can be sustained in the medium term."

The first is that it is not in the interest of the rest of the world, at this point in time, to stop sending their goods to the US and stop taking our dollars. In a great line, "...the United States is not hostage to the kindness of strangers, but rather, hostage to strangers acting in their own best interest."

McCulley thinks that a crisis will be avoided, but the readjustment to a more balanced current account will mean higher interest rates and a lower dollar, as well as increased inflationary pressures.

"What is needed to solve the current account problem is a big shift in the global pattern of economic growth, with the rest of the world growing faster and buying more from the United States, while the United States and its consumers slow down. Short of this, which is not a plan that is easily orchestrated, the solution is a dollar that falls so low that it has no place to go but up. That would reenergize the foreign private sector appetite for dollar denominated assets, attracting more permanent capital flows into the United States. Such a lower level for the dollar would, of course, be negative for U.S. consumers--hiking import prices and restoring some degree of pricing power to American producers in their home market. So inflation would also move higher."

In other words, things get cheaper and the world steps in to buy them. Even now, there are hordes from Great Britain who come to shop in the US, where prices for identical items are half of those in London or Dublin or Edinburgh. Eventually, that becomes not only goods, but companies and real estate. As the world's reserve currency, we are not in the same situation as an Argentina or a Mexico, where a serious all-at-once devaluation will be forced upon us. It will be slower, but it will come until a more new sustainable level is found.

"But such a further fall in the dollar need not become a crisis--as long as appreciating nondollar currencies are more painful to the rest of the world than a falling dollar is for the United States. As long as China and other emerging markets continue to be mercantilist [see "What Can Go Wrong: China" below] and want to keep their export-based economies growing, there is a reason for them to keep the dollar from falling sharply and their currencies from rising. And the mechanism to do this, selling the home currency and buying dollars, will continue to help fund the current account deficit gap.

"... So, in the long run, the unsustainable is still unsustainable. But between here and there, foreign central banks--operating in their countries' own mercantilist best interests--will happily buy dollars when foreign private sector investors do not want to fill the current account deficit gap. But right now foreign private investors are doing just that: playing the leading role in filling the gap.

"The United States is not begging for foreigners' savings; rather, foreigners are begging the United States to take their savings as de facto financing for the production of the goods and services that they are selling to us. This is certainly not the best outcome for the global economy, but the shame of it all is not only that we are consuming too much, but also that the rest of the world is manifestly consuming less than it could or should."

A Billion Here, A Billion There

"On most everyone's list of things to worry about, the federal budget deficit is pretty close to the bottom. That is why budget deficits could end up being a problem in the not too distant future--the 2020s. If the deficit is not seen as a problem, as it was in the 1980s, it will not be dealt with and that delay is what could make it a bigger problem later."

The old links between interest rates, deficits, and the bond market are broken. Politicians have no reason to think that deficits will cause higher interest rates (for good reason) and thus do not have the constraints felt in the '80s.

But as Paul acknowledges, the coming crisis in Medicare and Social Security will threaten the stability of the system. The current Congressional Budge Office estimate is that the deficit will "only" be $54 billion in 2012. But that assumes that the Bush tax cuts are rescinded and that taxes increase by $245 billion. If a tax increase of that magnitude were to happen, it is likely a recession would result. I think it likely that some form of tax cuts will be kept, although I think it is safe to say "the rich" will be paying more taxes. Ironically, as a result of the Bush tax cuts, the top 1% of taxpayers are paying more of the total tax receipts than during the Clinton years, and the bottom 50% are paying far less. The bottom half pay something on the order of 3% of total income taxes. The majority of that group pays nothing or gets tax credits.

It also assumes that a $54 billion dollar surplus in Social Security will offset that much in spending. In 2019, the Social Security surplus goes away.

There is a budget crisis coming. McCulley is a tad more sanguine than I am, as he thinks that Congress will act when confronted with a real problem. I happen to think it will be higher interest rates that will force their hand. We both agree that it will result in a combination of increased taxes, means testing of SS, and reduced spending.

Interestingly, Greenspan spoke at a recent PIMCO Client Conference. " 'We are talking potentially real concerns out there,' he said, referring to the fact that investors buying 30-year bonds now at very low yields do not appear to realize that they are taking on deficit risk in the decades ahead without being compensated for it. 'When does discounting begin?' he asked. 'You buy a 30-year issue now--you are buying a big chunk of that out there. That is my next conundrum.'

"There is nothing investors can do about the potential deficit problem now. It is often true in investing that even when you anticipate a problem correctly, there is not much you can do about it in advance, if most investors have decided not to worry about it for now. In fact, acting too early can be a big mistake. So, in the case of budget deficits, it will have to be wait and see, and be ready to act."

Bubbles, Bubbles Everywhere

At the turn of the century, we watched as a bubble in tech stocks developed and then burst. McCulley specifically suggests that Greenspan created the housing bubble as a way to finance consumer spending and to keep the economy on its feet while corporate America was in the dumps.

Will we have more bubbles? McCulley thinks so. There are three conditions that create the possibility for more: long periods of price stability (which stimulates the appetite for risk); the fact that capital is allocated through the market, which means the Fed cannot control the availability of capital (a good thing); and the Fed's unwillingness to step in to restrain or prick bubbles.

While it is too long to go into here, what follows in the book is a solid analysis of how the recent bubbles developed, the Fed's failure to deal with them, and the problems that resulted in the aftermath.

The next potential problem is that of recessions and the concern that in previous recessions there was an opportunity to use them to lower the trend of inflation, or opportunistic disinflation. During the next recession, there may be more of a deflationary problem.

But that there will be a next recession, we are both agreed. Congress has yet to repeal the business cycle, although I expect economic illiterate (and most embarrassing presidential candidate) Rep. Dennis Kucinich to introduce a bill to do so at any time.

But as to the timing, it is not clear. I still think we are going to look back and see the housing market as a cause of a recession. As an example of the problem, the Los Angeles Times reports that the most recent UCLA Anderson Forecast for California suggests that the housing market there may not return to "normal" until mid-2009, and job losses in real estate finance and housing will depress hiring through the middle of 2008, lifting the unemployment rate in the Golden State to 5.5%. That certainly corresponds to at least a mild, localized California recession. And I think that scenario plays out to a greater or lesser degree throughout the country.

What Economy.com calls "active" Mortgage Equity Withdrawal (MEW), or loans that are either cash-out financing or home equity borrowing, is down almost 50% in the first quarter of this year from the last quarter of 2005. With rates increasing and lending standards being tightened, we can expect MEWs to fall even further, providing a drag on consumer spending growth, especially retail sales minus energy costs.

What Can Go Wrong: China

"If it is not too much of an intellectual stretch to say that China is part of the monetary union that is called the United States-- the 51st state, if you will--then it is not too much of a stretch to say that what can go wrong is that China decides--or is forced--to secede.

"First, the 51st state. As noted earlier, China has kept its currency, the yuan, tied as closely as possible to the value of the U.S. dollar because that makes China's exports more competitive. But in doing this, China has essentially ceded the control of its monetary policy to the Federal Reserve, in the same way that all the 50 states in the United States have."

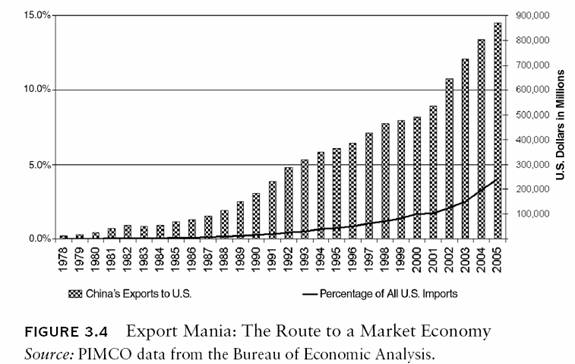

But the Chinese have done so for a very good reason from their point of view. It has allowed them to build a powerhouse export economy, with the US as their primary customer. The growth is illustrated in the graph below. The fact that the currency is undervalued gives foreign investors confidence to invest today in the hopes of getting bigger gains tomorrow.

As McCulley points out, this is a mutually beneficial situation. They get our dollars and then reinvest them in our bonds, which helps keep interest rates low.

"Ultimately, though, China will graduate from the American University for the Study of Capitalism. It will switch from a mass production economy to a mass production and mass consumption economy and have the courage and ability to free its exchange rate and shift away from its mercantilist model. So China will secede at some point. In fact, China took a first step in that direction in the summer of 2005 when it revalued the yuan by 2 percent, making it stronger against the dollar, and let it float marginally upward thereafter. That process was accelerated a little in the fall of 2006. These moves came under pressure from the United States, but China has only moved a little, so its special monetary union is still effectively a going concern.

"Even if secession is a slow process, interest rates and inflation will be higher than they would be otherwise. As the Chinese currency is allowed to appreciate against the dollar, their goods will become more expensive for Americans, and it is not clear how much competition from other emerging market countries will offset that upward price pressure. And as the yuan appreciates, China's central bank will be selling fewer yuan for dollars, reducing the dollar reserves that are recycled into the U.S. Treasury market. That means interest rates could be higher than otherwise.

"That is going to be unpleasant for American investors--but it should not be worse than that."

But McCulley notes that there is a danger to that scenario. What if we moved to expel them from the American School for the Study of Capitalism through wrong-headed protectionism, the kind which I discussed at length in last week's letter? Then that scenario could happen over a much shorter period of time and be quite disruptive.

Paul finishes the book with chapters on how to read the Federal Reserve, inflation, how his personally run portfolios are constructed, and - one of my favorite chapters - a brief discussion and quotes from some of the most important economic minds of the last century. That chapter was a true pleasure.

He amazingly discusses his tenure at PIMCO, both the good and bad. He discusses a great call he made but one that he did not weave into his portfolio (which would have only made a marginal difference) with a great one-liner: "I was long brains but short testicular fortitude."

The book is full of insights which will make you a better investor, like the following:

"And, finally, if you are going to keep some Treasury securities in your portfolio, consider buying them yourself, rather than through a mutual fund that specializes in them. The reason is simple: You can protect yourself against some unwanted losses.

"If you buy Treasuries through a mutual fund and interest rates start to rise, the fund is likely to sell some of the Treasury securities it is holding so it can buy securities with higher yields as interest rates rise. That raises the yield it can advertise. But the fund will be taking capital losses as it is doing this, because Treasury prices fall as yields rise.

"If you buy your Treasury securities yourself, you can avoid these capital losses by just holding the securities to maturity. If you do this, think about when you might need the money that goes into Treasury securities, so that you can buy maturities that you can afford to hold until they mature.

"It is very easy now to buy Treasury securities yourself, with no broker or commission involved. Just go to the Treasury Direct web site (www.treasurydirect.gov) and follow directions. The purchases are paid for by direct debt to your bank account."

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|