| Fun in the Subprime Summer |

| By John Mauldin |

Published

07/20/2007

|

Currency , Futures , Options , Stocks

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

Fun in the Subprime Summer

The State of the Credit Markets

The credit markets are experiencing their worst sell-off in five years. Yet, after all the hand-wringing, corporate credit spreads remain very tight by historical measures. Spreads on high yield bonds moved out to 312 basis points as measured by Merrill Lynch & Co., the widest level since December 5, 2006, but still not very wide at all in the larger scheme of things. Since falling to a record low of 241 basis points on June 5, spreads have gained 71 basis points. Merrill Lynch reported that high yield bonds lost 1.69 percent in June, which is hardly a big deal even if an investor is highly leveraged, as so many are today.

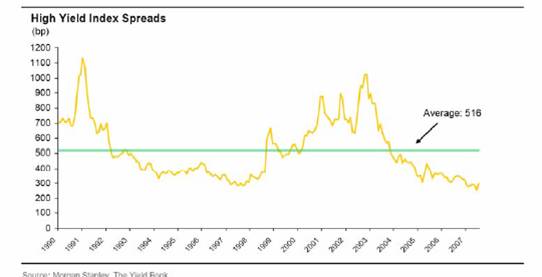

The following chart, courtesy of Morgan Stanley & Co., shows that high yield bond spreads remain comfortably below the long range average of 516 basis points. It should be noted that spreads also remained below average for much of the 1990s, but that was in a context where underlying interest rates were significantly higher than they are today, providing investors with higher absolute returns. Readers should also recall that tight spreads a decade ago led to a horrific sell-off as a result of the Long Term Capital Management mess, which revealed lax lending practices on the part of prime brokers to hedge funds. It is uncanny how reliably we can count on Wall Street to repeat the same mistakes. Instead of teaching marketing and other related subjects in business schools, it would seem far more sensible to require future business leaders, bankers and investors to study history and psychology. Perhaps some reading in Freud and Gibbon would give them the perspective necessary to avoid making the same missteps time and time again.

Even more dramatic than the 70 basis point drop in high yield bond prices has been the sell-off in the newly-minted LCDX North America index of loan credit default swaps, which was launched on May 22, 2007. This index, which is shown in the graph below (courtesy of Markit Group), tracks credit default contracts written on 100 syndicated secured first lien loans and has widened from a spread of 103.9 basis points at the close of business on May 22 to 228 basis points at the close on July 11. The LCDX had stabilized on July 12 as the financial markets, including the credit markets, rallied.

Many market observers attributed the credit market rally to short covering, although HCM would argue that the credit sell-off has been technical in nature and overdone from a fundamental standpoint. Unless something occurs to signal a genuine near-term deterioration in corporate credit quality, this sell-off may lose steam as investors begin to realize that subprime loans and corporate loans are completely different animals.

HCM understands that many dealers were shorting the LCDX index to hedge long exposures to bank loans that were being held in warehouse facilities; these positions placed additional downward pressure on the index, and any short covering will lift the price. In addition, hedge funds and other market players with long exposure to bank loans have been shorting the index to hedge their positions. LCDX appears to have become the new pricing benchmark for bank loans, which has further magnified its psychological importance to the market. On trading desks around the Street, all eyes have been on the LCDX, an instrument that didn't exist two months ago.

Madonna used to sing that it's a material world. Now she's gonna have to start singing that it's a derivative world. There's very little material about it. HCM would point out that from a fundamental standpoint it doesn't make sense for loan spreads to widen more than bond spreads. Bonds are, after all, lower down in the food chain of corporate credit and riskier than loans. The reason loan spreads have widened by 124 basis points while bond spreads widened by only about 70 basis points is purely technical in nature. Loan spreads are reacting more directly to the subprime meltdown than bond spreads because subprime loans and bank loans are ultimately owned by many of the same buyers through structured finance. Subprime mortgages have been packaged into subprime CDOs while loans have been packaged up into Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs).

Bonds are not significantly impacted by subprime woes because they do not enjoy cross-ownership with subprime paper through the structured product market. It could have been different had Wall Street gotten its way. In the 1990s, many bonds were owned by Collateralized Bond Obligations (CBOs) that were constructed on the basis of erroneous financial models. (CBO models were built on the assumptions that corporate bond defaults would run at 2 percent a year and default recoveries would average 40 percent of par. When these assumptions proved to be unrealistically optimistic, the equity in most of these deals was vaporized. Like the subprime CDO meltdown, the CBO disaster was entirely predictable ahead of time.)

Virtually all CBOs blew up, however, wiping out the equity investors and insuring that bonds will never again find much of a home in such vehicles except in the most narcoleptic of credit environments. The anomalous pricing movement between loans and bonds has occurred because today's credit markets are dominated by quantitative investors rather than fundamental credit specialists. Nonetheless, irrational price movements can (and if recent history is any indication, probably will) persist for a frustratingly long time. In looking at the relationship between the two markets, it appears that it might make sense to go long LCDX and short CDX (the high yield bond index) for two reasons.

First, a continued credit market sell-off (which is likely in view of the huge forward calendar of pending new issues, including gargantuan new issues for Cerberus Capital Management's acquisition of Chrysler Group and Kohlberg, Kravis & Roberts' purchase of First Data Corp.) should cause more damage in the unsecured bond sector than in the secured bank loan sector. In general, CDX should widen 2-3 points for every 1 point move outward in LCDX.

Second, bank loans have already seen a much larger move than bonds, which suggests that bond spreads should catch up and widen even further than loan spreads from this point forward. Speaking with some traders of this arcanum, however, HCM learned that this long-bank debt/short-bond trade was quite popular at the time of the birth of LCDX in May. While the trade initially drove the LCDX to a premium, it did not perform well and was unwound. Over time it may still make sense for those who are patient and unleveraged enough to wait for fundamentals to prevail. If one believes that there is truly going to be a significant repricing of credit risk, bond prices should widen significantly more than loan prices. But in the current climate, which can be charitably characterized as nervous, there probably aren't a lot of patient people around. Most people are just trying to limit their losses.

Sophisticated investors and readers of this publication (those two categories are hopefully synonymous!) should find this credit market correction neither surprising nor troubling. The damage that is being inflicted should be divided into two categories: permanent capital losses, which are largely confined to the subprime mortgage sector and related structured products; and mark-to-market losses, which are hitting other credit products, including high yield bonds, leveraged loans, and CLOs and CLO-squareds that own these securities. (A CLO-squared is best understood as a fund-of-fund of CLOs. It is a Collateralized Loan Obligation that invests in the liabilities of other CLOs. These are discussed further below.)

The subprime meltdown is the result of lax mortgage underwriting standards, fraud, undue reliance on rating agency imprimaturs, and an overindulgence in leverage. The difficulties experienced by two Bear Stearns hedge funds that apparently believed that it was not only prudent to invest in the riskiest subprime mortgages but to leverage these investments by a factor of ten may be the most embarrassing but hardly the only example of the reckless behavior in which bull markets lure even supposedly experienced investors to engage.

Mark-to-market losses on corporate bank loans are mostly a cause for concern on the part of hedge funds that have to report monthly performance, and for financial institutions that have to value their assets on a current basis. Fortunately, these paper losses have little or nothing to do with the underlying credit quality of the borrowers, which with very few exceptions continue to exhibit strong financial performance. Other than a few sectors that touch on the residential real estate sector, the U.S. and global economies remain relatively robust. Hopefully the sell-down will continue and offer investors an opportunity to purchase bonds and loans at even more attractive prices. If certain funds are caught with their pants down because they are overleveraged, that's the way the cookie crumbles.

The market is rightly punishing poorly structured deals (i.e. covenant-lite deals, asset-lite spread-lite deals, which for purposes of this discussion will be called "Lite Model" deals) more severely than more traditionally structured loans (i.e. loans with covenants and collateral). Just as investors in the subprime space are discovering that 2006-vintage mortgages are defaulting at higher rates than earlier vintage deals as underwriting standards all but collapsed in the last stages of the cycle, loan investors are coming to realize that 2006 and 2007-vintage loans that employed the Lite Model are problematic. Portfolios that avoid these types of loans should perform well over the next few years, while those filled with Lite Model loans, which are merely bonds disguised as loans, are likely to suffer greater volatility and higher losses upon default when the economy turns and default rates return to historical norms. At this point, however, it is important for CLO investors to understand that there is only a small likelihood that default rates are going to increase meaningfully in the next 12-18 months. Such an increase would require much weaker economic data than we have been seeing both in the U.S. and Europe in recent months.

According to Morgan Stanley, $54 billion of bond and $189 billion of loans are due to hit the leveraged finance markets in the next 4-5 months. These figures only include announced deals and do not include new deals that are hitting the market daily and will add to these record totals. In case anybody has noticed, mergers are continuing at a record pace. This week alone saw the announcement of several huge deals by both strategic purchasers and private equity buyers. There are few signs that the flood of deals, and the financing needed to complete them, will ebb. This huge forward calendar is one of the factors pushing bond and loan prices down.

There are also concerns about recent rate hikes by foreign central banks, the usual noises about geopolitical risks that at this point fall mostly into the Black Swan category, and general unease about the length and exuberance of the financial market run. Recently, markets have rejected a few of the more egregiously leveraged and aggressively structured deals, including U.S. Foodservice, Thompson Learning, and others. While this has caused some headaches for the private equity firms buying these companies, it has caused severe migraines for the Wall Street firms who were convinced to bridge the transactions in order to keep their highest fee-paying clients happy. It was inevitable that buyout firms would push the Street to bring deals to market with terms that stacked the deck so completely against the interests of lenders that at some point lenders would balk at the terms.

Now that this has happened, some people are asking whether underwriters will be willing to stand up to powerful buyout firms and tell them that they are doing nobody any favors by driving the market to the precipice with Lite Model deals. Even before global warming, HCM would have said that the odds of that happening were less than the chances of water freezing in hell. But in view of the fact that buyout firms paid $8.4 billion of fees to Wall Street firms in the first half of 2007 alone, it is more than a sure thing that lenders will have to look out for themselves and underwriters will remain beholden to the buyout kings. In protecting their own interests, lenders may want to remind themselves (and the credit rating agencies) that investors who lend money without receiving collateral and covenant protection have historically been considered to be junk bond investors, not banks.

Covenant-Lite Loans

A great deal of ink is being spilled on the subject of covenant-lite loans, which if memory serves correctly started appearing in the market in early 2005. These loans allow borrowers to operate with a great deal of impunity and leave lenders with few remedies in the event that a company begins to run into financial difficulty. Along with dividends paid out to sponsors that are financed with additional debt, covenant-lite deals are among the most anti-lender practices in which an equity sponsor can engage. The more powerful financial sponsors have been the most frequent users of these types of loans based on their excellent track records and reputations.

In other words, they have been able to dictate terms to the market. But in all fairness, such loans should not be problematic in every instance. From HCM's standpoint, a covenant-lite loan in a large capitalization company with a reasonable leverage multiple and decent asset coverage should not present a problem for a lender. In some recent deals that were rejected by the market, however, leverage multiples were through the roof, resulting in little or no asset coverage and a significant risk of principal loss in the event of a default. Such loans, if they are to be extended at all, should at the very least include covenants to provide lenders with the ability to limit the borrower's ability to do whatever it wants in terms of adding additional debt, paying dividends out to shareholders, etc.

There is room in the market for covenant-lite loans in a limited number of instances where the borrower is effectively of investment grade quality in terms of its underlying business and assets, and where the balance sheet is not unreasonably leveraged. In HCM's world, such companies are known as "fallen angels." But some of the deals being brought to market cannot be even charitably categorized as fallen angels - they are more appropriately described as ravished angels that may never be able to recapture their sacred state after the buyout firms have had their way with them.

Collateralized Loan Obligations

One might ask why the underwriting banks agree to move forward with some of the loans that have recently caused so much controversy and ultimately been turned back by the market. After all, even a rudimentary review of the credit profiles of some of these deals should have indicated that some of these credits were perilously leveraged and would require a lot of things to go right for all of their debt to be repaid. The main factor at work is that the relationship among the various participants in the market drives incentives in ways that may not always produce a rationale outcome with respect to each individual transaction. The fact that virtually none of these loans end up remaining in the hands of the banks underwriting them alters the relationship between the parties involved in these transactions.

If the banks can manage to get these loans or bonds off their balance sheet, they are no longer at financial risk (reputational risk is something they appear willing to bear). This alignment of interests is further reinforced by the fact that most bank loans today end up being owned by CLOs. Henry Kaufman pointed out several years ago that "widespread securitization" has had the broad effect of loosening the credit process. Credit standards have been lowered, and the credit market has grown enormously. This should not be surprising, given the role of the investment banker in the securitization process.

Mr. Kaufman also pointed out that widespread securitization has created a "liquidity illusion." "A securitized investment also encourages the investor to believe that he can quickly sell the obligation when a credit problem brews, thereby passing off the problem to someone else." But as he also points out, and as participants in the subprime CDO market are discovering to their dismay today, "[i]n volatile markets...liquidity may disappear suddenly, accurate pricing becomes exceptionally difficult to obtain, and marking to market may be practically impossible."

It is the investment banker's job to facilitate the securitization process - after all, his fee depends on the successful distribution of the issue - and in doing so, the investment banker's due diligence is limited by his analytical focus on the HCM is aware, of course, that banks do not technically "underwrite" loans in the legal sense that investment banks "underwrite" bonds or stocks. Banks syndicate loans by distributing them to a large group of other financial entities and generally retain little or none of the loan on their own books.

(HCM uses the term "underwrite" in this context because the banks that syndicate loans share with investment banks that "underwrite" bonds and stocks a legal duty to perform due diligence with respect to the borrower and retain liability with respect to the performance of that due diligence borrower's current financial situation. This, in effect, leaves much of the judgment in the hands of the investor.)

In a recent issue of GREED & fear, Christopher Wood further expounded on the dark side of securitization: "[Securitization] has one fatal flaw which will ultimately prove to be its undoing. This is that it removes the incentive of those making the loan to worry about whether the loan is a good credit. This is for the simple reason that the original lender sells the loan and gets paid up front as, by the way, do the credit-rating agencies. The more complex securitization becomes, and it has now become ludicrously complex, the further removed is the entity who owns the 'tranche' of debt from the entity which made the loan."

Mr. Wood actually overstates the case, because CLO managers are effectively original lenders and spend a great deal of time evaluating the credit merits of each loan. The problem that he is referring to occurs at the level of those investors who own the liability tranches of the CLOs. These are the tranches of debt rated between AAA and BB that are sold to finance a typical CLO.

Below is a simplified but representative capital structure for a CLO that owns a portfolio of bank loans with an allowance to hold up to 10 percent of the portfolio in bonds or so-called "second lien" loans, which are nothing other than unsecured loans that are properly understood as "bonds in disguise."

Simplified CLO Capital Structure

AAA Notes $300

AA Notes $20

A Notes $20

BBB Notes $17

BB Notes $15

Unrated Notes (Equity) $28

Total Capitalization $400

Today, many of the investors who purchase the riskiest debt tranches - the BBB, BB and Unrated Notes - are so-called CDO-squareds, or CDOs that invest entirely in tranches of other CLOs. The managers of these vehicles do evaluate the underlying corporate credits or mortgages in the deals in which they invest. However, they engage in quantitative analysis of the tranches of CDO debt they own based on financial models that calculate future probable default and loss scenarios based on historical data. The problem with this approach is that historical data is often unreliable in foretelling the future, and models often fail to anticipate future scenarios (as occurred at Long Term Capital Management).

There is a huge distance between the investors in the riskiest CLO tranches and the underlying investments on which the ultimate outcome of their investments depend. HCM would point to the disconnect between CDO-squared investors and the underlying collateral as one of the structural flaws in the structured credit market.

For that reason, however, it is important to distinguish between subprime CDOs and CLOs invested in corporate credit. It is tempting to paint these vehicles with the same brush, just as it is tempting to paint all covenant-lite loans with the same brush. The author of this report manages several CLO portfolios, so the following should be understood from the perspective of an active manager of corporate credit through several economic cycles. It is the CLO manager's responsibility and function to analyze and monitor each corporate credit in the light of changing macro-economic circumstances. Institutions that invest in a CLO are depending on the CLO manager to pick healthy credits and avoid defaults.

One of the reasons that bank loan prices are dropping and loan spreads are widening is that CLO buyers are backing away from the market in anticipation that loan prices will drop further. It is unlikely they are doing so out of fear that defaults will spike up. Firms ramping up new CLO deals have slowed down their purchases in anticipation that loan prices will weaken further, and there are market rumors that more than one warehouse facility has been terminated or put on hold.

From HCM's perspective, in the absence of credit weakness, a price correction in the market is long overdue; spreads have been too tight for too long. As a practical matter, wider loan spreads will also be necessary if the CLO new issue market is going to remain robust in view of wider CLO liability spreads. What remains an open question is whether lower-rated tranches of CLO paper are interesting investments at the current time. They have widened out significantly while the underlying corporate credits upon which their ultimate performance depends have not weakened materially (nor have their spreads widened meaningfully until very recently). Many investors appear to be waiting for corporate loan spreads to widen further, which is creating further pressure on CLO liability prices.

It is HCM's view that CLO liability spreads, particularly BB and BBB paper, represent good value today in portfolios that do not have an undue concentration of Lite Model loans. Investors can pick up 50-100 basis points of extra spread compared to what was available earlier in the year on this paper, and the underlying collateral risk they are buying has not increased significantly. This opportunity has been presented by the contagion effect caused by the fact that buyers of this paper also own a surfeit of subprime CDO paper. Smart investors who can withstand mark-to-market volatility should take advantage of this opportunity to invest with savvy loan managers who are taking advantage of the current sell-down to pick up loans at the first discounts the market has offered in a long time.

The Economic Outlook for Leveraged Credits

The underlying health of most borrowers remains robust, and without an increase in defaults, the problems that are plaguing the subprime CDO market will not be repeated in the CLO market. Based on the work of Morgan Stanley, one can argue that there were some signs of economic weakness in the first quarter of 2007 but far from anything that would support an argument that serious problems are imminent. From a portfolio manager's perspective, there is plenty of room to avoid potential credit difficulties and investment losses.

Morgan Stanley found that the average cash cushion (calculated as the percentage of cash divided by debt) for companies in the widely used high yield derivative index HY CDX had slipped by March 2007 to slightly below the average for the March 1998-March 2007 period of 6.75% for the first time since March 2002. Debt amortization schedules for companies in this index are back-loaded, which is favorable for borrowers and suggests minimal default pressure on issuers (and also reflects the power balance in favor of debt issuers in the marketplace). At the same time, the firm found that the average interest coverage for companies in its high yield coverage universe is hovering slightly above 3.5x, which is in the upper range of coverages for the last decade.

Overall leverage for companies in Morgan Stanley's coverage universe ticked up and also hovered just above 3.5x in the March quarter, roughly equal to where it was in the fourth quarter of 2006 but definitely higher than it was by 0.25x or so earlier in 2006. Real weakness is only apparent when the firm drilled down to specific industries, where technology, metals and mining and homebuilders showed significant deterioration in their liquidity metrics (cash divided by debt) year-over-year. Overall, Morgan Stanley's analysis shows that economic fundamentals are hanging in there but that there are signs that weakness is cropping up in certain areas that bear watching. From a portfolio manager's perspective, however, this should not raise a great deal of concern, particularly if one is managing a CLO and focusing on senior secured credit risk. Managers of unsecured and subordinated credit risk always have to use a sharper pencil since their downside risks are much greater when the economy exhibits softness.

The New Mickey Mouse Club

Many people have been watching with great concern the takeover of the Gaza strip by Hamas, a terrorist faction of the Palestinian people. Nothing better signifies the demented psychology of these new rulers than Farfur, the bizarre, puffed-up version of Mickey Mouse that stars in the Palestinian children's television program, "Tomorrow's Pioneers." The program is broadcast on the Hamas-affiliated Palestinian television channel Al-Aqsa.

The tuxedo-wearing Farfur's favorite activity is to teach children how to read while preaching worldwide Islamist revolution and violence against Jews. He also encourages audience participation in his program, urging his young audience to call in and sing songs about the destruction of Israel. In the show's final episode, the squeaky-voiced rodent was killed off in a scene that could have been pulled out of the pages of the Protocols of Zion.

Earlier in the episode, Farfur's grandfather gave Farfur the deed to some land to safeguard. He tells his grandson that this land was inherited from Farfur's grandfather's ancestors and was occupied in 1948. "The Jews called it Tel Aviv after they occupied it." Later in the episode, Farfur is interrogated by an actor portraying an Israeli investigator. The investigator demands that the mouse hand over the deed to the land given to him by his grandfather.

Farfur responds, "These are the land documents which my grandpa entrusted to me, so that I would safeguard them and use them to liberate Jerusalem...I won't give them to criminal despicable terrorists!" The Israeli then beats the helpless mouse to death. Toward the end of the episode, Saraa, the young girl who serves as hostess of the show, declares that "Yes, our children friends, we lost our dearest friend, Farfur. Farfur turned into a martyr while protecting his land. He turned into a martyr at the hands of the criminals and murderers."

It is always valuable to try to understand the psychology of one's enemies. Where better to identify that psychology than in the lessons that a society tries to teach its children. If the Palestinians ever hope to join the world of civilized nations, they are going to have to choose a different path than the one Hamas is offering them.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|

|