| The Subprime Virus |

| By John Mauldin |

Published

07/28/2007

|

Currency , Futures , Options , Stocks

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

The Subprime Virus

As predicted in this letter early this year, the credit markets have finally begun to tighten, as a major re-pricing of risk is underway as a direct result of the subprime markets. The subprime virus seems to be spreading, despite the view a few weeks ago that there would be no "contagion" in the rest of the credit markets. This week we look at the re-pricing of debt and take a rather positive view and explain how a bottom in the credit market is reached. As ugly as it looks on Friday afternoon, it's not all that bad yet.

What credit derivatives have taken away, credit derivatives may in fact give back. We look at market volatility, rising interest rates (yes, you read that right), the yen carry trade and more. And I show my penchant for foolishness by making a mid-year forecast on the markets. I also offer you a chance to make your predictions against the pros. All in all, it is a lot of ground to cover, so let's jump in.

But first, a quick comment about the recent drop in the stock market. 520 points on the Dow sounds like a lot. It certainly gets a lot of breathless attention on CNBC. But good friend and South African partner Dr. Prieur du Plessis writes in his latest blog that the recent volatility is not all that special. Thursday saw a drop of 311 points. He writes:

"Since the start of the Dow in 1896 we have seen a drop of more than 312 points on 15 occasions. This is really not a very meaningful statistic as one should rather look at the percentage decline to take cognizance of differing index values over the decades. On this basis last night's decline rates as only the 698th largest in history. Put in another way, we have seen drops of this magnitude or worse on 2.5% of all trading days over the past 111 years."

The current volatility is large only in comparison with the last five years, which have been rather remarkable in their bullish consistency, with very few serious pullbacks. While as noted below, I think the market is going lower in the short term, this is nothing that should be seen as all that unusual in the longer term scheme of things. And now let's see what fools (especially your humble analyst) these mortals be.

2007 Mid-Year Forecast

"Where," I have been asked, "is my usual mid-year forecast?" The answer is that I have been waiting until after my trip to Maine to make them as that trip gives some context to the process of making predictions.

As some of you know, David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors, for several years has been holding an annual fishing trip to Maine for professional investment types. Various media have attended over the years, and one of them gave it the name The Shadow Fed, and for whatever reason, it has stuck. The tradition has been that on Saturday night everyone gathers and makes predictions (with small $5 bets on the predictions) about where the various markets will be at next year's event.

A little background. This year's gathering included Martin Barnes of Bank Credit Analyst, Barry Ritholtz (often quoted here), John Silvia, the chief economist for Wachovia, several hedge fund managers, mutual fund managers, traders of various sorts, a columnist from Barron's and a senior Federal Reserve economist, about 20 in all this year. Most of the group "runs money."

I take my youngest son Trey, and it is one of the highlights of our year. We get up in the morning, go fishing with a local Maine guide and everyone meets on an island where we eat what we caught plus a lot more the guides bring, drink a little wine and then go fishing in the afternoon, meeting back at the lodge (more below) for a gourmet meal (which is to say too many calories) and more wine.

(Everyone ships in more wine than they can drink so there is more than enough, although Martin, being Scotch, decided that we would need a few wee drams of single malt after dinner and graciously provided. There were some 100 odd bottles for the 20 or so of us, which may or may not help the quality of the conversation, although it certainly helps the intensity.)

This is a busman's holiday for everyone (for non-US readers, that is a vacation during which one engages in activity that is similar to one's usual work). The majority of the talk is rather intense discussions of the economic world on a rather wide variety of topics. David has a knack for finding people who are serious students of the market. It is rare that one gets such a time to spend hours discussing the markets at length with no pressure on actually needing to meet a deadline.

So, with that as background, we gathered after dinner on Saturday to make our predictions and see how we did last year. Last year we had 5 categories and this year we had 8.

As an average the group did not do too badly, although the range of predictions was rather wide. (For what it's worth, I was closest to the euro-dollar exchange rate, although I obviously was very wrong on the Dow.)

But the interesting thing to me was the "volatility" of the winners. Most categories would have had different winners had we held the "close" for the contest a month earlier. And yet again different winners if we had held it two weeks earlier. Kotok would have paid me on a side bet we had earlier this year on the S&P if we used today rather than last Friday.

"Winning" was almost a random event. You had to get the direction right, and most people did. But then getting closest to the actual number on the Dow or the euro or interest rates was difficult when the there were ten other people who had the right idea and were guessing in the same neighborhood as you.

Before we get to the predictions, let's look at a few quotes from Nassim Taleb's new book, The Black Swan. I am slowly digesting this remarkable work and suggest that any serious student of the market do so as well. I will be doing a more lengthy review at some point in September, but you should get the book. You can go to www.amazon.com.

Let's look at a few selected paragraphs from the beginning of the book:

"The inability to predict outliers implies the inability to predict the course of history, given the share of these events in the dynamics of events.

"But we act as though we are able to predict historical events, or, even worse, as if we are able to change the course of history. We produce thirty-year projections of social security deficits and oil prices without realizing that we cannot even predict these for next summer - our cumulative prediction errors for political and economic events are so monstrous that every time I look at the empirical record I have to pinch myself to verify that I am not dreaming. What is surprising is not the magnitude of our forecasts errors, but our absence of awareness of it. This is all the more worrisome when we engage in deadly conflicts: wars are fundamentally unpredictable (and we do not know it). Owing to this misunderstanding of the casual chains between policy and actions, we can easily trigger Black Swans thanks to aggressive ignorance-like a child playing with a chemistry kit.

"...To summarize: in this (personal) essay, I stick my neck out and make a claim, against many of our habits of thought, that our world is dominated by the extreme, the unknown, and the very improbable (improbable according our current knowledge) - and all the while we spend our time engaged in small talk, focusing on the known, and the repeated. This implies the need to use the extreme event as a starting point and not treat it as an exception to be pushed under the rug. I also make the bolder (and more annoying) claim that in spite of our progress and growth, the future will be increasingly less predictable, while both human nature and social "science" seem to conspire to hide the idea from us."

So, the above quotes will help put the later predictions into context. By definition, we cannot know the future. Yet we go through the exercise. And even though we should know that we will probably be wrong, there is a value on the process if done with the proper amount of cautious optimism tempered by reality.

I think about the future not just to look for opportunities to invest but primarily as a thought process to assess wherein lies the risk. The first task of an investor is to manage risk and only secondarily to seek attractive returns. We make predictions about the future so as to think about risk and to seek places for opportunity. And then every so often, we re-assess our predictions in the light of new information and adjust our risk controls and objectives.

So, with that being said, let's look at what the average prediction for various markets was of the group and then my own. Note, that when you made a prediction, you made a $5 "bet," so we all had minimal skin in the game, but as with all such ventures, it is the bragging rights that are the real driver to spur seriousness.

Let's start with Fed funds. The group on average thinks that rates will more or less stay the same, at 5.18%. Since I think the economy will slow down, I guessed that Fed funds will be lower at 4.5%. That also reflects that I think the Fed will be on hold longer than most observers currently think, as inflation is still a concern. They will not start the cutting process until next year.

Risk? If Fed fund rates are much lower, then that means the economy is doing worse than I think it will. This is one area where the difference in the group is interesting. About half think that rates will rise and the other half thinks they fall or stay the same.

The average prediction for the ten year bond is 5.53%, and I am at 4.5%, again reflecting my view that the economy is softer.

We had two dates for the S&P 500. The first was for September 15 and the next was for next year. The group average prediction for September was 1468. I was at 1375. (The S&P closed today at 1456. I think it was at 1522 last Friday.) For next year, the group is again at 1468 and I was still at 1375. If there is a recession, my thinking is the market will drop from here and then begin to climb.

By the way, the divergence of opinion in the S&P 500 was dramatic. One rather bearish fellow (whose current investment book is net short, for what that's worth) is thinking 989 next year, while a few exuberant souls see the market at well over 1700.

Oil is tagged at $68 a barrel, and here I decided to game the bet a little. I decided to put in a deliberately high number on the chance there will be some kind of a problem and that oil will rise above where it would normally be. I was high at $84. Interestingly, Barry Ritholtz guessed $83.75. Barry and I did take some side bets on the over/under for the group.

The euro was pegged at $1.37, more or less where it is today, and I forecast a small rise at $1.44. There are some gold bulls in the room, with the forecast at $742 and my modest projection at 745. CPI was interesting. The average prediction was 2.61%, although the range was from 1.62% to 3.5%. I was at 2.7%, which on reflection is probably way too high. What was I thinking? I need a mulligan on that call.

Compete With the Pros

What would you have predicted? Give me your numbers for the eight categories and we will put it into a spread sheet and see what my readers predict. Send me your name and email address and predictions in the following 8 categories: Fed funds rate, 10 year government bond, WTI crude oil, S&P 500 on September 15, S&P 500 on July 18 of next year, the euro, gold and CPI. I will post the average in a later letter.

Closest to the pin (actual numbers) will get a copy of whatever my favorite book is at this time next year. I will make a side bet with Kotok that my readers do a better job than our group. But then, we have a handicap. We are professionals.

A few thoughts on this. I can guarantee you that my projections will be different 90 days from now than they are today, and different yet again in 6 months. Why? Because I will have new information. Things will likely change. The chances of me being right on any of these numbers is not entirely random, but close enough that there is little mathematical distinction.

When the Facts Change

John Keynes, upon being confronted by someone that he had made a different prediction than what he held a his current view, is famously quoted as having said, "When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?"

And I think that everyone in the group would agree. While we take the "game" of investments very seriously, if you do this long enough, you will get humbled quite often. That is why you constantly evaluate your analysis, and change them when the facts change.

And the credit markets are changing their opinion in a very rapid manner. Earlier this spring, the credit markets started to get concerned about subprime mortgages. But "everyone" said it would not spread to the rest of the credit markets, so there was no cause for concern. I was not so sanguine. I have consistently thought that the entire credit markets would be affected, through a tightening of credit standards. And now the markets are starting to agree. Let's look at a few charts, and then think through the opportunities, especially in the high yield space.

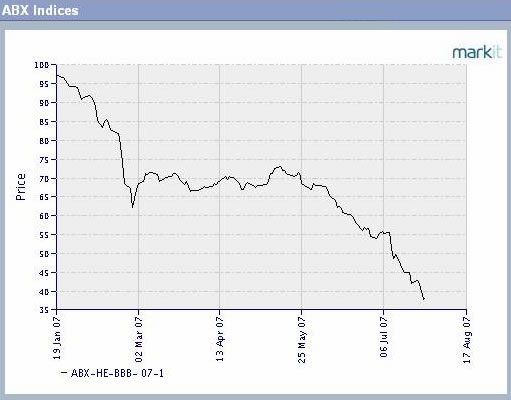

Let's first look at the BBB paper in the mortgage markets. It is now trading at less than $.38 cents to par (100), and that chart is still pointing down. Catch a falling knife, anyone?

The Subprime Virus

But that is just the subprime stuff, John. A few weeks ago, no one thought it would spread. But spread it has. And spread is the correct word. Spreads on high yield bonds have widened. By spreads I mean the difference, or spread, between the yield on a bond and its corresponding yield on a government bond (of the same time frame). If a high yield bond had a spread of 300 basis points, or 3%, then it would be yielding 3% over the government bond.

Let's look at this next chart, which is the spread on credit default swaps on high yield bonds. Note that the spread has risen from below 250 basis points as recently as early June to almost 500 basis points this morning. That also means that high yield bonds have dropped in value by almost 9% from the high, which was slightly over par less than two months ago!

In other words, less than two months ago, the average trader and manager did not think there was any risk in the high yield space, or at least there was historically less risk than at any other time in history.

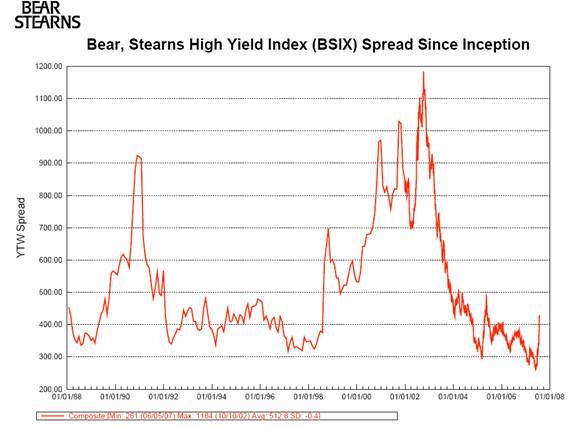

So, let's look at the next chart to put this into perspective. Let's look at this chart from Bear Stearns (courtesy of good friend, business associate and high yield maven Steve Blumenthal of CMG) which shows high yield spreads for the last almost 20 years. Now, this is a different index than the Markit CDX high yield, with different underlying bonds, but the point is to show that even though yields have almost doubled, they are still not all that high by historical standards.

Now, even if you take out the ugly periods in 2001-2 which were caused by Enron, WorldCom, etc. it would still take another sharp rise just to get back to the average yield spread.

Now, Steve tracks yet another high yield index. It reached a low in late February of this year of a spread over treasuries of only 209 basis points. Today it is at 504! That is a significant move! And the spreads are widening. They could easily (and probably should) go higher.

So, what stops them from going back to the 2001 yield spreads? Just as CDOs and subprime derivatives have made the markets more volatile and risky, Credit Default Swaps on high yield bonds will soon have traders licking their chops in anticipation.

First, let's point out that defaults are at an all-time low. Corporations are generally in better shape than they have been in a long time in terms of being able to manage their debt. Even in a slowing economy, there is not reason to think that defaults are going to rise back to 2001 levels.

Let's start with a very simplistic analysis. Say you're a high yield trader sitting at a fund or a prop (proprietary trading) desk at a major investment bank. You can buy $40 million of high yield bonds yielding almost 5% over cost by putting up just $10 million in collateral. You get 5% on you margin capital and a total of 20% ($40 million x 5%) on your invested capital from the excess yields on your bonds (which you probably bought as a credit default swap, avoiding the time consuming hassle of buying the actual bonds). You are making a total of 25% on your money.

So far so good. If the bonds drop 2.5% in value, you are down 10% on your margin money but still making a net 15% over a one year period. However, if they drop 10%, you are down 40% and it will take two years of those high yields just to recover your initial capital, if you and your investors can stand the pain and the margin calls.

But what if you were leveraging a few months back when yield spreads were just 200 basis points? You were getting a total of 13% returns (4 x 200 basis points on the spreads plus your 5%). Not very juicy, but respectable in a low return world. But then the market falls outs, and drops by 9%. You are now down almost 36% of your original capital, and it will take a long time to get back to even, assuming you can hold on that long, and of course assuming you meet your margin calls. Otherwise you take the losses.

And that will be the game over the coming months. The underlying debt that creates the credit default swaps in the high yield space is well defined and transparent. You can bet that there is a lot of work being done on the credit quality of each of those bonds that comprises the index. At some point, traders step in and decide the risk is worth the reward, and the market stops falling.

By the way, this whole market is a fairly recent development. You couldn't do this even five years ago in any size and with any liquidity. Now any Tom, Dick and Harry fund or prop desk can do it. But if trader's think the market is going lower, they will wait.

Credit? What Credit?

Over 40 Leveraged Buy Out (LBO) deals have been pulled in the past few weeks. The biggest investment banks are having to "eat" the paper on the Chrysler and Boots LBOs, as they cannot find buyers for the paper. In essence, they committed to lend the money and planned to sell the bonds into the market, keeping fat fees and commissions. Now, they have to put the loans onto their books.

This is not all bad. It simply means they have to use their own capital, and at yields lower than they could get today, to fund the deals. It is not that the paper is bad. It is just that the market wants a higher yield, and the banks would have to lose money to sell at the higher yields.

But what it does mean is that now the banks have less capital to fund new deals, and that private equity funds will have to pay more interest and put more equity into a deal to get it done. That makes a lot of deals less attractive than they were a few weeks ago.

Part of the sell-off in the stock market is from stocks which were thought to be "in play" but are now no longer take over candidates. The wind in the sails that has been private equity and buybacks is dropping, as funding is drying up rapidly.

Issuance of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) soared to a record $57 billion in the first half of 2007. That has since slowed to a trickle. So far this month, just $1.9 billion of CLOs have been sold, according to Standard & Poor's Leveraged Commentary & Data. "Leveraged finance's cash engine -- the CLO market -- has ground to a halt," S&P noted in a written commentary on July 19. (WSJ Online)

CLOs prices, like high yield bond prices, have dropped in the past month. Just last month they were priced over par. Now the index is down about 6%, as yields have risen from a spread of a little over 100 basis points to almost 350. That is a major change. And this is on loans, gentle reader, which are generally senior to bonds and usually have some type of collateral baking them.

This simply illustrates that all the credit markets are acting in tandem. Part of the reason is that the margin clerks are demanding increased collateral on the riskiest loans, and when there is a crunch you sell what you can and not necessarily what you want. That is why nearly every asset is going down in tandem - stocks, bonds (except for government debt), commodities, gold, etc.

This is acerbated substantially by the unwinding yet again of the yen carry trade, as the yen is rising rather rapidly against a host of currencies and those who borrowed long yen are rushing to the exits only to find everyone else trying to get out the same small door.

The yen was almost 124 to the dollar almost a few weeks ago. Now it is below 119, a drop of over 4% in a few weeks, which is huge in the world of currency trading.

If you are leveraged long the yen to invest in the Australian or New Zealand dollar (or whatever your poison of choice is), you are now down 3-4% times the amount of your leverage in just a few weeks. That is also putting pressure on the markets.

In short, it is going to be a while before credit markets stabilize. They will, of course. But it means businesses are going to be paying higher rates for loans, mortgages are going to be harder to get (and now cost 50 basis points more than they did a month ago), and fewer deals are going to get done.

The subprime virus has spread. The markets are getting a fever, and like most viruses, it will simply have to run its course.

Next week, we will look at what all this means for the economy, but the short version is that it will mean slower growth in the last half of the year.

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. Contact John at John@FrontlineThoughts.com.

Disclaimer

John Mauldin is president of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors before making any investment decisions.

|

|